The Harlequin Ladybird was first discovered in New Zealand in 2016 and the population has made its way from Auckland, where it was first found, down to Marlborough and other southern wine regions. The pest represents a big threat to winegrapes and strategies are being created for producers to fight back. Journalist Harrison Davies explores how to manage this new threat.

on damaged grapes.

Photo: R Brewster &

K Ker

Harlequin ladybird derive their names from the white patterns found on their head which resemble the faces of clowns.

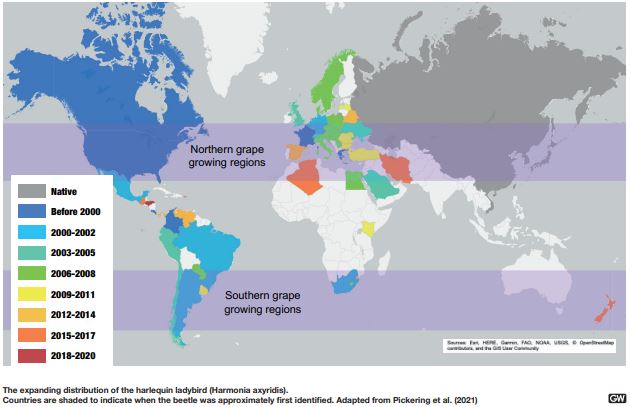

Originally hailing from South-East Asia, the species has been introduced to every continent across the globe and has become a notable pest in wine regions across the world.

In places like Europe and America, the insect was introduced as a way to fight back against aphids as it prays on them.

However, it was soon discovered that the omnivores also had a taste for grape, and the abundant fruit found in vineyards more than satisfied their hunger.

Harlequin Ladybirds were discovered New Zealand in 2016 and quickly spread throughout the North Island in the ensuing years.

Populations of Harlequins were recorded in Marlborough in the months following Cyclone Gita in 2018 and clusters of them have already been reported in Marlborough vineyards.

Whilst the influence of Harlequins has not yet been felt by producers in New Zealand, management processes have already begun to prevent the pest from having a major impact on the local wine industry.

What’s the danger?

Harlequin Ladybirds can effect grapes by clustering around them and eating damaged fruit, where they then get mixed with the berries and crushed into the wine.

This results in what researchers describe as ‘ladybird taint.’

Ladybird taint is recognised as an unpleasant aroma and taste in wines that has been likened to burnt peanut butter.

Professor Gary Pickering from Brock University in Canada is the leading expert on the species within vineyards and their effect on winegrapes. He said different varieties can expect to be affected in different ways.

We get a lot of reports of

sightings and have been

working with Plant and Food

Research to undertake some

monitoring in Marlborough,

Hawkes Bay and Nelson

to understand more about

how and when the ladybirds

are using vineyards as their

habitat.

– Sophie Badland

In his study he added multi-coloured Asian ladybeetles (MALB) to red and white juice and must and had a professional wine tasting panel describe the results.

“White wines displayed higher intensities of bell pepper, asparagus, and peanut aroma and flavour compared with control wines, while red wines showed higher intensities of peanut, asparagus/bell pepper, and earthy/herbaceous aroma and flavour,” Pickering said.

“At the same time, bitterness (more intense), sourness (more intense), and sweetness (less intense) were also affected in MALB-treated red wines, while in whites the intensity of fruit and floral descriptors was reduced compared with control wines.

“These effects increased with the number of beetles added to the juice/must.”

The study showed that each cluster of grapes, on average, needs to be exposed to roughly 200 grams of beetles for taint to be affected.

“Ladybird taint can be detected with as little as one beetle per vine, and because they are so small it is very easy for them to sneak through,” Pickering said.

“[Ladybirds] don’t damage grapes, full stop, we’ve done work to show that what they [actually] do is feed on pre damaged grapes.

“So if you get swelling, or detritus or wasps, or hail or whatever that scale integrity is gone, then they can feed off the sugar.

“The problem occurs once the bugs are incorporated, crushed and pressed.”

Pickering added that clusters of beetles were attracted to vertical habitats, and that environments with an abundance of vertical plants and structures could encourage populations to the area.

Reports of Harlequin populations, particularly in Canada, has been reported in wineries adjacent to soy bean fields and properties bordered with willow trees.

“They get into vineyards through proxy as from adjacent habitats, and don’t congregate, and vineyards because grapes are cool but because their primary food source isn’t available anymore,” he said.

In many places where Harlequins were introduced to fight off aphids they have ended up a more dominant species, also trimming away native ladybird populations.

Once the soya beans have been harvested and the habitat for the aphids removed, the harlequins would seek shelter amongst grapevines.

Once in the vines, they are equally harvested alongside the grapes and crushed into the wine, where they excrete ethoxy pyrazines.

Pickering’s research has found ways to treat wine affected by ladybird taint and he discovered that the methods they explored have multiple applications.

“One of the attractions of do work in this field is that this thing compounds that can ruin your wine from ladybugs are also compounds that are found naturally in some grape varieties,” Pickering said.

“If you come up with a fix for later bad times, then that can also be applied just for routine winemaking.

“There’s some initiatives around removing methoxy pyrazine wounds from juicing wine that are getting close to being commercialised, seeing them commercialised.

“There’s some specialty polymers that people are working on, remove just methoxy pyrazines from wine. That’s exciting.

“Seeing that commercialised to me is important, because it’s not just the way to treat what we call the bandwagon.

“It’s a way to treat wine that has been made from grapes that haven’t achieved optimal ripeness.”

A growing population

Countries like New Zealand and Australia put a lot of work in to prevent pest populations from entering their ecosystems and horticultural industries.

Experts are unsure of how the Harlequin ladybirds first arrived in New Zealand.

Biosecurity Manager for New Zealand Winegrowers Sophie Badland said that while no damage had been reported on any winegrapes at the time of writing, extensive efforts were being made to ensure producers were protected.

“The harlequin ladybird arrived in NZ in 2016 and the population distribution is still changing from year to year, based on the reports we get,” she said.

“There’s a lot we don’t yet know about the insect and how it will behave in New Zealand in the future, so we will continue to keep an eye on the situation and ensure growers are prepared to take further action should it become necessary.”

Once the population of Harlequins were first discovered it was quickly realised that the population was already established; the tools required to prevent further spread were insufficient.

Ladybird taint can be detected

with as little as one beetle per

vine, and because they are so

small it is very easy for them

to sneak through.

– Gary Pickering

Biosecurity New Zealand recovery and pest management manager John Sanson explained to Stuff in 2019 that the official strategy would be management, rather than prevention.

“When first alerted to the presence of the harlequin ladybird in April 2016, MPI began an investigation, which determined that the pest was already well established,” he said.

“It was also determined that containing or slowing the spread was not feasible due to limited effective management tools being available.

“MPI (Ministry of Primary Industries) stood down the investigation and has undertaken no further operational measures. We have however continued to liaise with the pip fruit and viticulture industries to provide information and support.”

Since then a population of the ladybirds has become established in Marlborough.

The first step taken by New Zealand Winegrowers has been to educate producers about what to look for and to assist people in keeping populations of the pests away from vines.

“New Zealand Winegrowers has been regularly putting awareness material, including identification guides, into industry communications to ensure growers are aware of the potential threat posed by the Harlequin,” she said.

“We’ve discussed it with growers at biosecurity workshops and asked people to report sightings to our biosecurity team, so we are aware of where the ladybirds are and the timing of their movements.

“We get a lot of reports of sightings and have been working with Plant and Food Research to undertake some monitoring in Marlborough, Hawkes Bay and Nelson to understand more about how and when the ladybirds are using vineyards as their habitat.”

Reports of damage from the Harlequins out of California and Europe in the last few years have prompted a strong response from New Zealand Winegrowers.

The majority of sightings and reports have been lodged in the winter months, when the beetles congregate in sheds.

However, Badland did say that a number of reports had been made of Larvae being found on vines in the spring.

“To date, we have seen no issues from the harlequin ladybird through the vintage season. In Canada and the US we know they will sometimes aggregate in grape bunches prior to harvest, causing taint in wine made from affected bunches,” she continued.

“However, we have not seen this behaviour from the harlequin ladybirds in New Zealand – rather, over-wintering aggregation is happening after harvest and any large clusters of ladybirds are usually found in sheds, containers and other vineyard outbuildings.

“Throughout the growing season, we get reports of growers finding harlequins in the vines, but it is usually eggs, larvae or small numbers of adults and these seem to leave the vineyards well before harvest.”

Pickering added that prevention was the best method of keeping the beetles away from grapevines.

“Awareness of the quality of your fruit in terms of damaged fruit and if you get damaged fruit that looks like there are some there are olfactory cues that might attract the bugs,” he said.

He also said that it would be important for producers to ensure there were no beetles mixed with the harvested fruit.

“If you are hand harvesting, sorting tables have been very effective. In fact, some producers have manufacturing, sorting tables specifically to remove Ladybug taint from fruit,” he said.

“On the other end machine harvested fruit, some optical scanners which wineries are already using to get rid of mould and stuff that’s not grapes can also be effective at getting rid of Lady Bugs.”

Countries are shaded to indicate when the beetle was approximately first identified. Adapted from Pickering et al. (2021)