Australian Vintages McGuigan Zero range now makes up 10 per cent of sales of the entire McGuigan portfolio.

The challenge in making good quality, no and low alcohol wine

In the July issue of the Grapegrower & Winemaker, we published Part 1 of Sonya Logan’s exploration of the no and low alcohol wine scene, which described the New Zealand wine industry’s efforts in this space, particularly its Lighter Wines initiative. In Part 2, Sonya looks at the methods of producing no and low alcohol wines and talks with the Australian producers behind a zero, low and lighter alcohol product to find out where their journeys have taken them.

It was late in 2018 when the idea of entering the alcohol-free wine category was raised at Australian Vintage. Having experimented with alcohol-removed wine over the previous 20 years, the company decided there was consumer demand for good quality, zero alcohol wine that it could satisfy.

Twelve months later, McGuigan Zero was launched comprising a Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, Shiraz, rosé and sparkling. And the response by consumers has meant the McGuigan Zero range now makes up 10 per cent of sales of the entire McGuigan portfolio.

“We knew there was consumer demand for ‘better for you’ options and, understanding the category, we knew there was an opportunity to lift the bar of quality offered, but the popularity of Zero has completely exceeded all our expectations,” remarks Australian Vintage’s chief winemaker Jamie Saint. “The popularity just keeps growing and now our challenge is to make sure we have enough stock to supply our customers.”

There’s no doubt about it, there is a distinguishable growing interest in no and low alcohol wine products in Australia. The Endeavour Group recently reported that sales of non-alcoholic drinks — those containing less than 0.5% ABV — in its BWS and Dan Murphy’s outlets increased 83% in the month of June 2021 compared with July 2020, with beer followed by wine the best-sellers in the category. Low alcohol wine specifically, that is wines ranging in alcohol from 0.5% to 1.15% ABV,

grew 45%.

This demand inspired the recent opening of Australia’s first alcohol-free bottleshop in Sydney’s northern beaches and non-alcoholic bar in the Melbourne suburb of Brunswick East.

Acknowledging that consumer interest in no and low alcohol products is “growing intensely”, senior scientist with the Australian Wine Research Institute, Wes Pearson, said the challenge for the Australian wine industry was to make products that “fill that niche” or risk losing consumers to other offerings in the category.

“Traditionally, a lot of the [no and low alcohol] products have been pretty average and maybe have scared away consumers; they tried them in years past and thought, ‘Oh, that was terrible, I’m not going back there’,” says Pearson.

“There’s some consumer data that shows when people look to no and low alcohol wine, if they don’t find what they want they go to beer or spirits in the category instead where there are lots of innovative and well-made options. That says to me that we need to do some work in this area to win these consumers back because there’s potentially a demographic that’s not being serviced. “We don’t want to lose wine drinkers, we want to keep them drinking wine.”

Pearson says compared to other drinks industries in the category, the wine industry has been “lagging behind” in responding to the growth on offer. But he admitted this was largely due to the capital costs involved in producing low and no alcohol wines.

Australian Vintage chief winemaker Jamie Saint with the company’s spinning cone column.

Innovation ‘a problem’

“Innovation’s a problem in this sector because it’s expensive to play in. Innovation [in the wine industry] has often been driven by smaller producers — bespoke producers who are doing things in their shed, mucking around and making some cool products. They don’t have the risks that bigger companies have in investing the time and inputs and staff…so they can try something and fail and they’re not as worried about it.

“But that innovation hasn’t happened in this category because the smaller players haven’t been able to afford the technology to do it. So, we haven’t seen that little undercurrent of innovation from those smaller producers, other than things like piquette where grape skins are rehydrated, fermented out, then bottled. But that’s not wine — that’s a grape-based beverage.”

In Australia, labelling regulations state that a regular wine is anything that contains 4.5% ABV and above; between 0.5-1.15% ABV is regarded as a low alcohol wine, while anything less than 0.5% ABV can be labelled non-alcoholic, alcohol free or dealcoholised. The regulations vary in overseas markets, however. For example, in the UK, the alcohol threshold for table wine is 8% ABV, low alcohol is 1.2% ABV or below, wine labelled alcohol free must contain no more than 0.05% ABV, while de-alcoholised wine must be no more than 0.5%.

Pearson says there have been two techniques favoured by most wineries in Australia and around the world used to remove alcohol: reverse osmosis and spinning cone column.

“Reverse osmosis tends to be used for alcohol adjustments more than dealcoholisation. The sensory effect of removing large amounts of alcohol with reverse osmosis is that you end up with less intense sensory characters.

“The spinning cone column is probably the industry standard for dealcoholisation down to 0.5% or 0.05% ABV. You get a better sensory result using those products. It’s gentler and it’s done at a cooler temperature.”

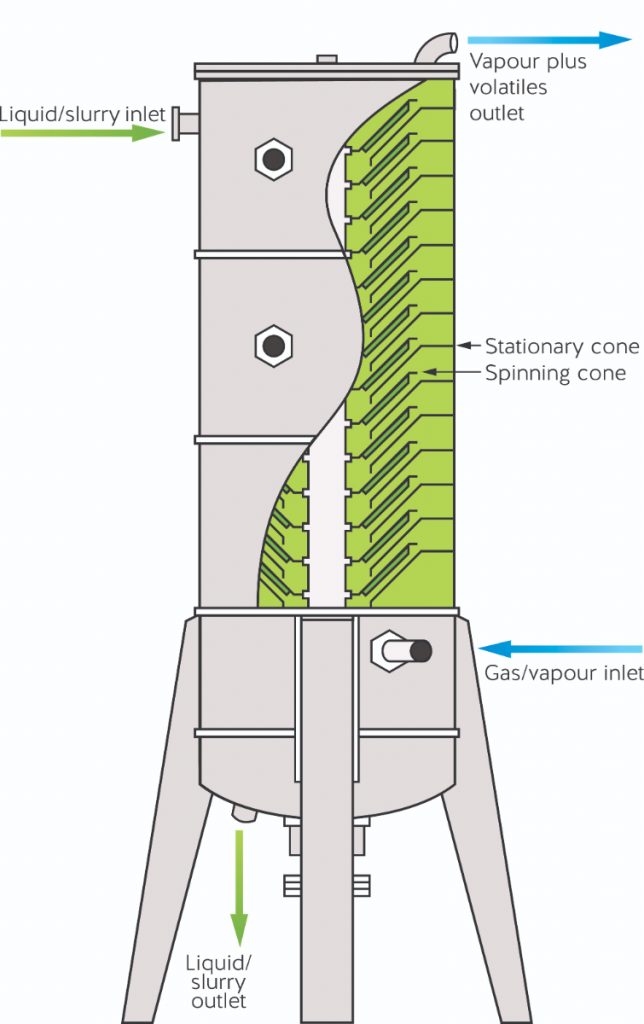

A global leader in spinning cone column technology is Australian company Flavourtech, based in Griffith, New South Wales, which specialises in the manufacture of technology designed to recover, extract and evaporate aromas for food, beverage and pharmaceutical products. Flavourtech was established in the 1980s for the express purpose of commercialising spinning cone column technology that had been developed by the CSIRO. The initial application of the technology was for removing sulfur from grape juice during the winemaking process. But, one day, Flavourtech co-founder Andrew Craig was asked whether the spinning cone column could also be used to remove alcohol from wine.

“It did work and it worked really well,” remarks Flavourtech’s global sales manager Paul Ahn. “[Craig] was standing next to the condenser at the time and could smell the lovely varietal aromas being extracted. And, so, he decided he should look into this aroma aspect of the spinning cone column as well.”

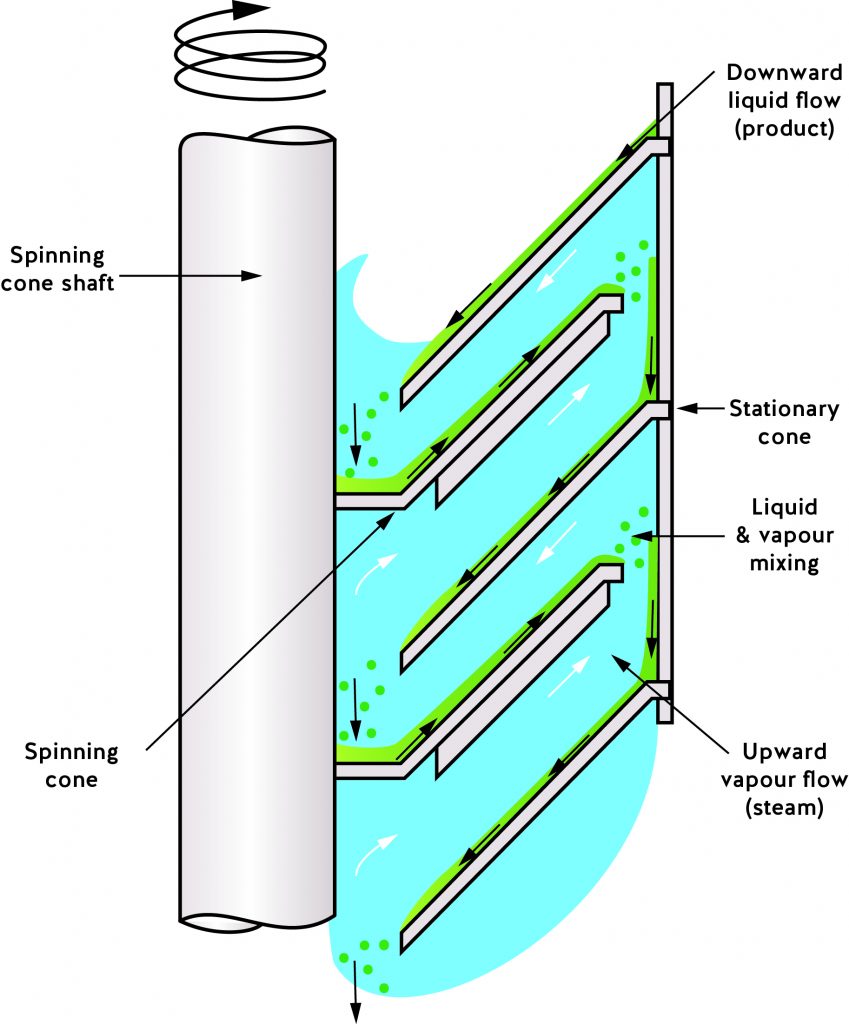

While a few refinements to the technology have been carried out since, the fundamentals remain the same. The spinning cone column (SCC) is a multi-stage distillation process that uses steam to strip, in this case, wine of alcohol. Inside its stainless steel body lies a central rotating shaft and a number of alternating stationary and spinning cones attached to either the wall of the column or the shaft. Wine is fed into the top of column and onto the first stationary cone. It then falls down the cone by gravity and onto the spinning cone directly underneath whereby it is flung upwards and outwards by the centrifugal forces of the spinning cone. The wine then hits the wall of the SCC and falls onto another stationary cone directly underneath, and the process continues down the column.

At the same time, steam is introduced at the bottom of the SCC and flows up, carrying with it the volatiles, namely the aroma compounds and alcohol, from the wine. These volatiles are then condensed and stored while the dearomatised and dealcoholised wine exits from the bottom of the column. The aroma compounds can subsequently be added back to the wine.

Flavourtech’s SCC process is carried out under vacuum, meaning the temperature of the column and steam are kept low, between 30-45°C. Ahn explains that wine is in the column for less than 30 seconds and this, combined with the low operating temperature, ensures the process has minimal or no impact on wine.

He says the recent surge in popularity of low and no alcohol beverages has brought with it a rise in the number of inquiries Flavourtech is receiving for its SCC, including from the wine industries in Australia and New Zealand. While Ahn agrees that the cost of technologies capable of producing low and no alcohol wines has been a barrier to uptake by smaller producers, Flavourtech has endeavoured to overcome this by releasing smaller SCCs.

“We now have three sizes. Our smaller size is what we call the Spinning Cone Column 100, and the price starts at just over $400,000. Wineries can now afford to start on a smaller unit but then expand to different sizes as they start to grow and increase sales of their products.”

Ahn says winemakers are beginning to pay closer attention to lifting the quality of their zero and low alcohol products.

“In the past we were seeing winemakers who were asked to produce a low or zero product sending a low quality wine through. We always say, what you feed in is what you get out — low quality in, low quality out. But now that consumption of low and zero alcohol wine is increasing and some of those products are winning awards, we are seeing winemakers send a better quality product through, so we are seeing increasing flavours, increasing quality coming through to the market, which is benefitting consumers as well,” says Ahn.

It is the application of a spinning cone column that has resulted in McGuigan Zero.

“The spinning cone column is the equipment of choice to remove alcohol from wine because of its gentle nature,” Jamie Saint explains. “However, where we have learnt to focus, from our experience, is understanding the process and then adjusting our winemaking at the base level to prepare it to undergo the alcohol-removal process.

Understanding changes and effects

“Ultimately, changes occur to the style of wine when alcohol is removed. The more we can understand these changes and effects, the more appropriately we can prepare our full-strength base wines to undergo the process and be best balanced stylistically on the other end.

“We need to mimic the sensations from alcohol that are lost during the process to ensure we still have a great tasting product — a product that tastes as expected for the varietal, just without the alcohol. For us, this is all achieved through winemaking technique and understanding that central alcohol removal process.”

Buoyed by the success of McGuigan Zero, in June this year Australian Vintage launched a new lower alcohol range of wines under its Tempus Two label called Lighten Up. With an ABV of 6.8%, the range includes a Prosecco, rosé and Pinot Noir and, like the McGuigan Zero, were made using the same spinning cone column technology.

“McGuigan has now grown to become the number one selling alcohol-free wine in Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom and we want Tempus Two to be a leader in the lower-alcohol category,” Saint says.

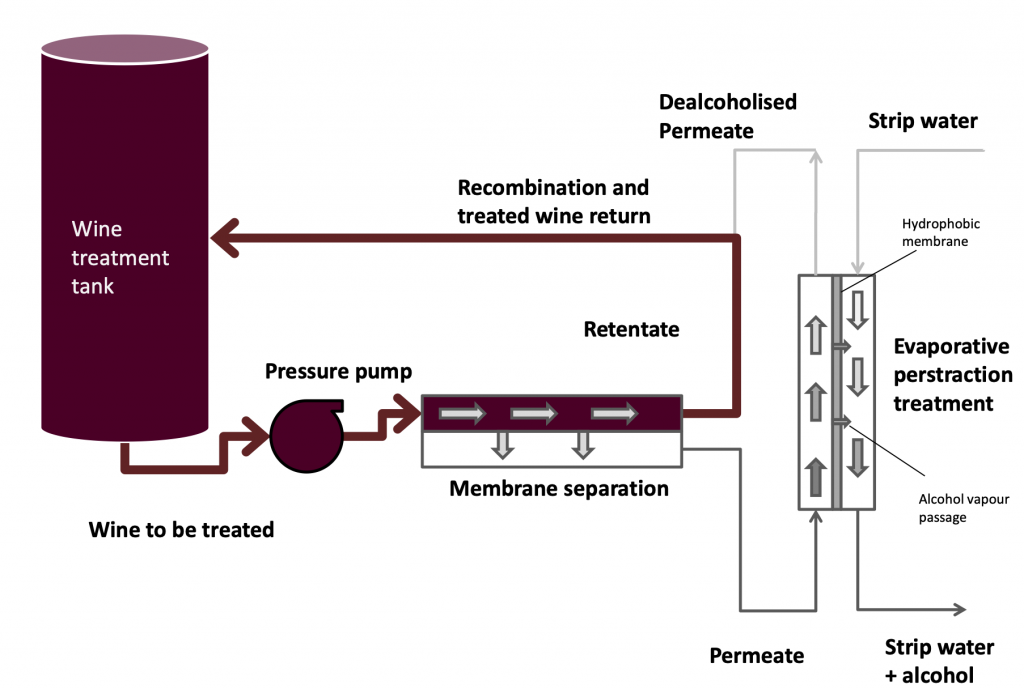

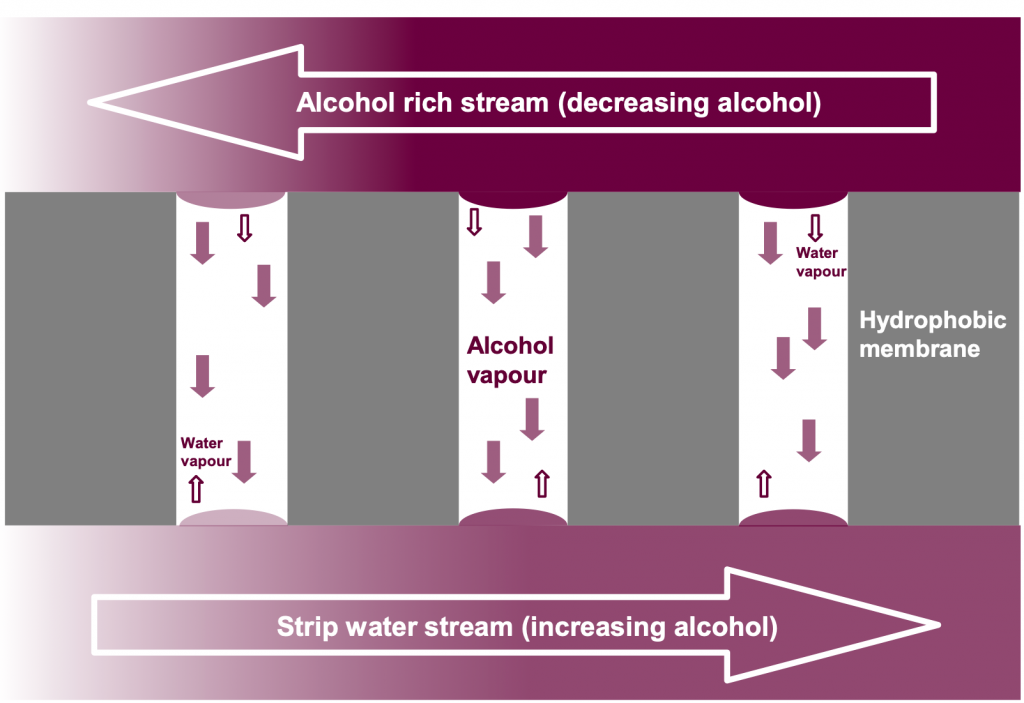

VAF Memstar is another Australian-based company with a history in the treatment of wine to reduce alcohol. Its ethanol reduction process, which was developed in the mid 2000s, utilises nanofiltration, a variation of reverse osmosis which separates wine into a concentrate and a permeate. The concentrate retains virtually all of the colour, tannin, flavour and most of the alcohol of a wine, while the permeate comprises water, some of the alcohol and a few minor components. The permeate is passed through a second membrane where most of its ethanol is stripped out and then it is recombined with the concentrated wine, resulting in a lower alcohol product with minimal loss of aromatics.

“Our two-stage process has proven to be, over many years, very successful here and around the world,” remarks the developer of the process and VAF Memstar’s research and development manager David Wollan. He emphasises that “by itself, reverse osmosis [or nanofiltration] does not remove alcohol. In fact, it increases wine alcohol concentration. Alcohol reduction involves more than just reverse osmosis. If you don’t treat and recombine the dealcoholised permeate with the wine concentrate, as in the Memstar process, then you must remove the permeate and replace its volume with water. This second approach is of dubious regulatory status and leads to lower quality product. That’s why I think some reverse osmosis has a bad reputation.”

Wollan said what the Memstar process was “really good” for is trimming alcohol —reducing wine by anything up to about half its original alcohol level.

“So, if you’ve got a wine starting out at 15%, to get it down to 8% is feasible and practical with that process. Anything less than that though is not practical. Where our process really works best is dropping 1%, 2% or 3% alcohol just to get it right rather than make a low alcohol wine.”

Wollan says that the way the membrane process operates means there’s a limit to how much alcohol can be removed from wine.

“If you want to move something through a membrane, you’ve got to have a concentration difference on one side of the membrane compared to the other to have a driving force for the separation. If you haven’t got a big concentration difference, it’s actually very hard to get that sort of driving force across a membrane, meaning to achieve very, very low alcohol wines as you approach zero alcohol, you’ve got a very small difference of alcohol content across a membrane. So, it’s actually very hard to get down to those very, very low levels,” states Wollan.

.

Casella Family Brands has applied reverse osmosis in the production of its lower-in-alcohol [yellow tail] Pure Bright wines, which was released in June. Comprising a Pinot Noir and sparkling with an ABV of 10.8% and 8.5%, respectively, the wines were also released onto the US and Canadian market earlier in 2021.

“Our winemaking team has been trialling the production of low alcohol wines since 2015,” David Joeky, winemaker at Casella Family Brands, tells Grapegrower & Winemaker.

“The production of [yellow tail] Pure Bright started towards the end of 2019. [It] was developed to provide a lighter, more refreshing alternative with fewer calories and less alcohol when compared to our core range, which meets consumer demands while also attracting a younger demographic.

(Left) The [yellow tail] Pure Bright range is currently available in a sparkling and Pinot Noir. (Right) Casella Family Brands winemaker David Joeky.

.

“An increasing number of consumers are interested in health and leading more balanced lives,” Joeky continues. “In particular, younger consumers are looking to moderate their overall alcohol consumption, whilst others are looking to reduce their calorie intake while not compromising on taste or quality.

“We also know that regular wine consumers have increased their frequency of wine consumption at home due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a trend that is expected to continue for the next few years beyond the pandemic.”

Joeky explains that various methods in addition to reverse osmosis have been applied throughout the grapegrowing and winemaking process to achieve incremental reductions in alcohol for its Pure Bright range.

“Our vines are selected and pruned to maximise the leaf protection from the sun, protecting the grapes and slowing their development whilst maintaining fruit flavour and intensity. The grapes are picked earlier, while they have a lower natural sugar content, converting to lower alcohol in the wine. We also implement night harvest to keep the grapes cool and crisp in order to maximise the aroma and flavour.

“The grapes are run through a cooler fermentation process using specialised yeast to maximise the flavour profile at lower alcohol levels. Finally, our wines are blended by our winemaking team utilising our reverse osmosis process and other techniques to deliver a balanced, great tasting lower alcohol wine.”

Joeky says that while white varieties and light-bodied reds have responded better to the alcohol targets Casella’s winemaking team have been trying to meet, reds have proved trickier to achieve the desired alcohol level without losing balance in the wine and the tannins increasing.

“However, after lots of development work, we released the Pure Bright Pinot Noir which we are really proud of. The ultimate goal of [yellow tail] Pure Bright is to maintain quality so a lot of trialing is done to ensure the quality remains in the wines we choose to release in the range,” says Joeky.

He says that while it is too early to determine any trends in [yellow tail] Pure Bright sales in Australia, the company has seen “a good pick up” from the varieties launched in the US and Canada, which also includes a Pinot Grigio, Sauvignon Blanc and Chardonnay. Given the success of the brand in those countries, Joeky says Casella will look to potentially extend the Pure Bright range in Australia with new varietals in the future.

David Wollan said VAF Memstar had developed a distillation system that would likely be available to industry in a matter of months. The system comprises a low vacuum, low pressure, low temperature column that the company is confident will remove alcohol down to almost zero without also stripping out volatile flavours.

However, Wes Pearson says the industry still has a way to go before it can claim the holy grail of a high quality zero or low alcohol wine. Whilst he believes there are “a lot of options” around the alcohol levels of the [yellow tail] Pure Bright range, the lower ranges still remain a challenge.

“I think there’s lots of options at [8-9%] alcohol; there’s no doubt for me that we can work at that percentage and make some products that look pretty close to wine that are good alternatives. But, the holy grail is to get to zero and still have products that look like wine. Currently, those wines are just not there yet,” says Pearson.

“Whilst we haven’t got it totally figured out, we’re doing pretty well with flavour. We can get flavour back into wines after most of their alcohol has been removed, but there’s still potential to improve on the texture, to give consumers that richness that comes from ethanol being in the mix.

“So, what can we add to these wines? People are adding different kinds of wine-based things, such as grape skin extract, tannin and grape concentrate. Traditionally, that’s been a big thing — add some sugar to try to get some mouthfeel back. But, if you’re trying to appeal to a health-conscious consumer, high levels of sugar may not be the best answer.

“I think some products work better than others. Sparkling wines, whites, they’re probably easier than the reds. Reds present a formidable challenge to figure out how to replicate wine.”

Wollan agrees: “Alcohol is one of the important balancing components in wine. If you just take the alcohol out, it’s like cutting off one leg of a chair. If you think of the legs of a chair as alcohol, tannin, acid and sugar, if you take out just one of them, then you unbalance that wine. And that’s why, consistently, most of the tastings of zero or very low alcohol wines have not been particularly satisfying, because people imagine that you can take a wine, a good Barossa Shiraz or Coonawarra Cabernet, take out the alcohol and then somehow it remains like that. It doesn’t work that way, especially with red.”

Australian Vintage’s Jamie Saint says the biggest learning for his company during its zero alcohol journey has been that achieving quality, varietally-styled, alcohol free wines starts “well before the alcohol removal”.

“You can’t put any wine through an alcohol-removal process and expect it to work. You must undertake suitable winemaking adjustments beforehand to ensure that what is produced on the other side is within expectation.

“Without giving too much away, we need to try to replace all the characteristics like sweetness, warmth, viscosity and mouthfeel that alcohol contributes to wine. So, using various winemaking techniques, we produce wines specifically for the alcohol removal process so that, post alcohol removal, they are balanced and contain the important characteristics that make wine, wine. We are using our experience to adjust wines to a point that may look awkward as full-strength wines, however will be balanced and stylistically in the zone post the alcohol removal process,” Saint says.

Diagrams explaining how VAF Memstar’s technology removes alcohol: (left) this highly magnified schematic cross-section of a wall of a tubular membrane shows the migration of alcohol through microscopic pores, from a high concentration stream to a lower concentration stream on the inside of the tube; this process is known as evaporative perstraction and (right) alcohol reduction by reverse osmosis and evaporative perstraction where water is used to strip alcohol from the permeate stream of reverse osmosis processed wine. This permeate is then recombined with the wine from which it was extracted, thus lowering the alcohol of the blend.

Left: Flavourtech’s Spinning Cone Column is a multi-stage distillation column that employs steam as the stripping medium. It consists of a stainless steel body, central rotating shaft and 20 sets of alternating stationary and spinning cones attached to either the wall of column or the shaft. And (right) the dealcoholisation process.