By Tony Hoare

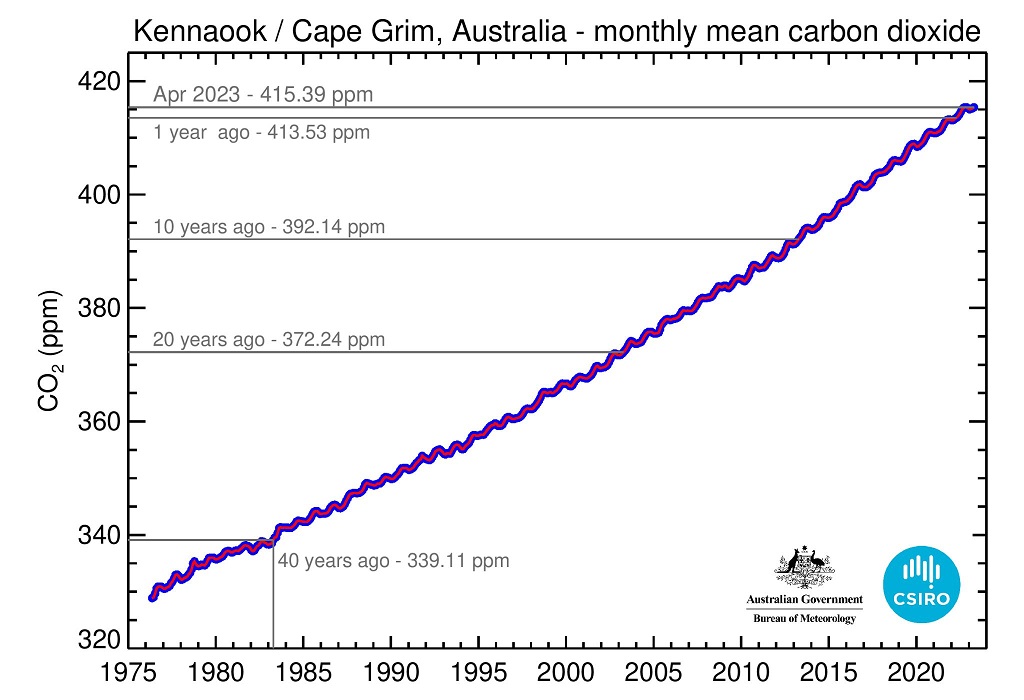

Now that the green house gas (GHG) emission reduction targets have been set and the countdown to meet those targets has begun, how do winegrape growers fit into this new carbon economy?

There seems to be a lot to unpack around this topic. This will undoubtedly create more work for growers and require their careful consideration about how to act to decarbonise and reduce other GHG emissions or, alternatively, increase carbon sequestration in their businesses to either become carbon neutral or a seller in the carbon credits market.

Understanding the overall processes and where you fit in as a business is important to ensure that the most appropriate pathway into the carbon economy is chosen to deliver the best outcomes for your business.

The diverse range of winegrape growing enterprises in Australia means that there will be different motivation and means for addressing GHG emissions. As winegrape growers there are two pathways to take at present in the carbon economy. The first is becoming carbon neutral by reducing GHG emissions through changing current practices as well as supplementing any shortfalls towards carbon neutral by purchasing carbon credits, also known as ‘offsets’. Carbon neutrality will become mandatory for winegrape growers in Australia by 2050 as the wine market falls into line with international export markets as well as various government, industry and social expectations and regulations and timeframes for GHG emission reductions.

GETTING STARTED TO REDUCE GHG EMISSIONS IN VINEYARDS

With the target of zero carbon emissions by 2050, there is a relatively long lead time for Australian winegrape growers to achieve GHG emissions reduction targets compliancy. Wine Australia is currently developing an emissions reduction roadmap for the grape and wine sector. In the meantime, there are plenty of resources to begin the process of auditing your carbon footprint and beginning positive action to reduce GHG emissions in your vineyard business.

A valuable publication has recently been released specifically for viticulture by Integrity Ag and Environment. ‘A Guide to Carbon Footprint Assessment for South Australian Viticulture Production Systems’ is viticulture-specific guide and a great reference for winegrape growers starting to look at GHG emissions and the carbon economy. Australian Grape and Wine, together with South Australian Wine Industry Association (SAWIA), also released a great guide in 2010 which is still relevant today: ‘A Guide to Greenhouse Gas Reduction for South Australian Grapegrowers & Winemakers’.

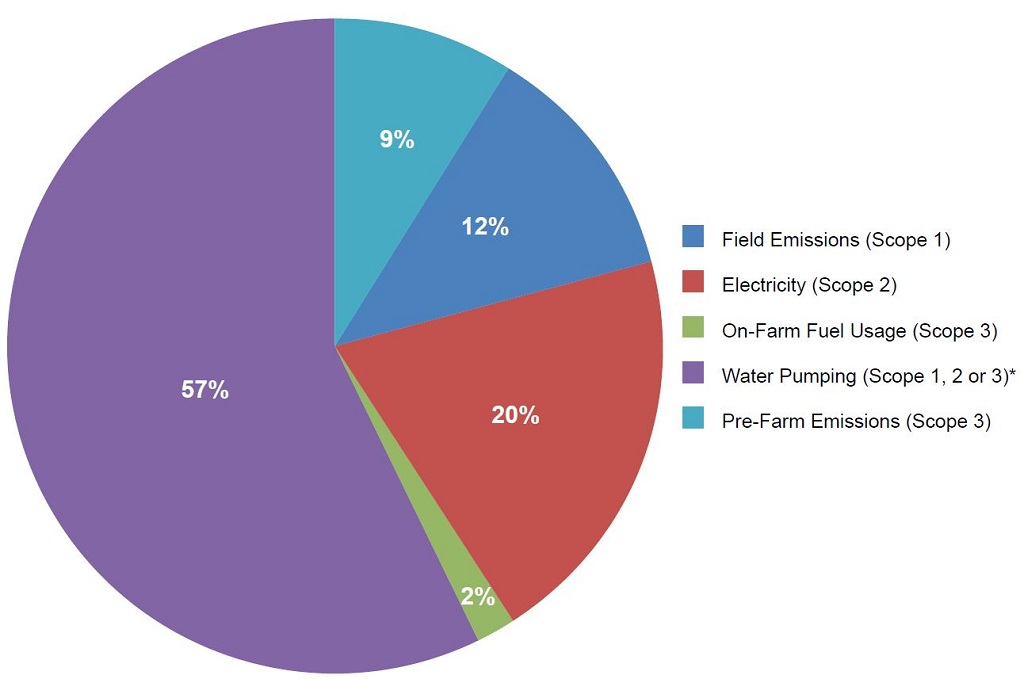

A useful resource for performing your own carbon accounting benchmarking exercise and establishing your baseline carbon footprint is the Australian Wine Industry Carbon Calculator. Calculating your carbon footprint allows identification of Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions and identification of the ‘hotspots’ of high GHG emissions. Strategies can then be considered to reduce those areas of your business responsible for causing the majority of emissions. Beginning to decarbonise your vineyard in preparation for certification can start at any time and deliver reduced GHG emissions as well as improvements to productivity and improvements in sustainability credentials.

The two ways to achieving carbon neutrality are either to decarbonise aspects of the business or, if this is not possible or practical, to purchase offset carbon credits. Keep in mind that the best emission is the one that doesn’t occur and purchasing carbon credits is seen by some as giving GHG polluters a licence to pollute. The practice of ‘greenwashing’, whereby a business makes false or misleading environmental claims, is under the microscope at present from not only consumers but authorities protecting consumer interests, such as the ACCC. Wine Australia also has guidelines around making carbon neutral claims and ensuring that those claims are validated and legitimate. Ideally, the best way to carbon neutrality is to reduce carbon and other GHG emissions by baselining GHG emission levels and understanding where the areas of pollution are occurring.

According to the recent publication ‘A Guide to Carbon Footprint Assessment for South Australian Viticulture Production Systems’, which is based on the outcomes and feedback from a study conducted for South Australia’s Department of Primary Industries and Regions (PIRSA) and a series of pilot carbon accounting workshops run in early 2022 throughout the state in conjunction with Ag Excellence Alliance: “Reducing emissions in Australian grapegrowing operations should typically focus on optimising inputs, primarily electricity use, fuel use, water use, and purchased inputs (such as nitrogen fertilisers, herbicides, and pesticides) relative to yield developing options to use less emission-intensive input”.

The reduction of GHG emissions in vineyards can begin by focussing on some key areas. The use of nitrogenous fertilisers is a significant contributor to GHG emissions in vineyards. Nitrous oxide (N2O) is the byproduct of nitrogenous fertilisers, animal excreta, legumes and soil cultivation and has 310 times the global warming potential of carbon dioxide. Improving the efficient use of nitrogen fertilisers, minimising soil cultivation and improving soil fertility, drainage and overall structure through increasing soil organic matter (carbon) are all positive steps towards reducing this potent GHG emission. Reducing nitrous oxide emissions from agriculture is the focus of a current study at the Primary Industries Climate Challenge Centre based at the University of Melbourne (piccc.org.au). A trial is currently under way in the Quelltaler Estate vineyards in the Clare Valley, South Australia, examining the potential of plasma technology to extract nitrogen from the atmosphere to be stored in water and used for agricultural production. The low energy consumption and high output production rate, which is scalable, has the potential to provide ‘green nitrogen’ for agriculture in the future.

PlasmaLeap’s plasma device to extract

nitrogen from air into water.

Valley, South Australia

Fuel for vehicles is the major source of GHG emissions in vineyards. Although all on-farm vehicles contribute, tractors are the major GHG emissions polluter in vineyards. Most growers already keep tractor use to a minimum so the risk in making further reductions is that the vineyard may suffer in the short term through jeopardising a crop and in the long term through taking shortcuts in vineyard operations, such as weed management. A good place to start looking at GHG emissions and tractor use is to keep track of the hours and mileage for various operations and consider alternative practices. Weed control is a good example of where reductions in tractor operations can be achieved through practices such adopting undervine mulch, the use of an ATV for herbicide application instead of a tractor or the use of sensor technology such as the WeedSeeker, a selective weed spray device which allows an increase in tractor speed during spraying and a reduction in herbicide volume.

The other major seasonal tractor operation in vineyards is canopy spraying for fungal and insect pathogens. For most growers the number of spray passes will depend on seasonal disease pressure influenced by climate conditions. Reducing the amount of spray passes and diesel tractor use is a risk and reward scenario. To have the confidence to remove a spray or increase spray intervals a grower must weigh up the cost savings of chemical, fuel, labour and GHG emissions versus the risk to the vineyard of reduced yield or fruit quality from disease. The new era of electric tractors is fast approaching to ‘fix’ the GHG emissions from diesel tractors however, until electric tractors become more within reach, other strategies to reduce spray passes could be considered. Ensuring spray efficiency and efficacy are maximised through spray coverage and chemical dosage is the best place to start by ensuring correct sprayer operation. Attending a regional spray application workshop or engaging the services of an expert, such as Don Thorp at Hortspray, might allow a reduction in spray frequencies and reduced GHG emissions without increased risk to crop loss.

One other significant source of GHG emissions in vineyards is the use of electricity to pump water in irrigated vineyards. Emissions from pump use can be offset in a number of ways. If it is not viable to add photovoltaic (PV) power to harvest solar energy for pumping then it may be possible to purchase ‘green energy’ from a supplier. Maximising water use efficiency also maximises electricity use in pumping.

To maximise water use efficiency to reduce electricity usage an important starting point is the pump itself. Is your pump fit for purpose and operating at maximum efficiency? An audit of your irrigation system performance will allow you to assess your system efficiency. Check both ends of the system by evaluating emitter uniformity which is as simple as timing output with a bucket placed either under a dripper, or the midrow of a vineyard if you have overhead sprinklers. Good hydraulics are essential for maximising pump efficiency and vice-versa.

A good place to start is your local irrigation experts. Or, an independent pump efficiency expert can provide assessment of your pumps’ efficiency or run courses to train you or your staff how to do it yourself. Rob Wellke is an Australian-based international expert who offers courses in hydraulic and pump performance assessment and optimisation (www.talle.biz).

South Australia.

Source: A Guide to Carbon Footprint Assessment for South Australian Viticulture Production

Systems

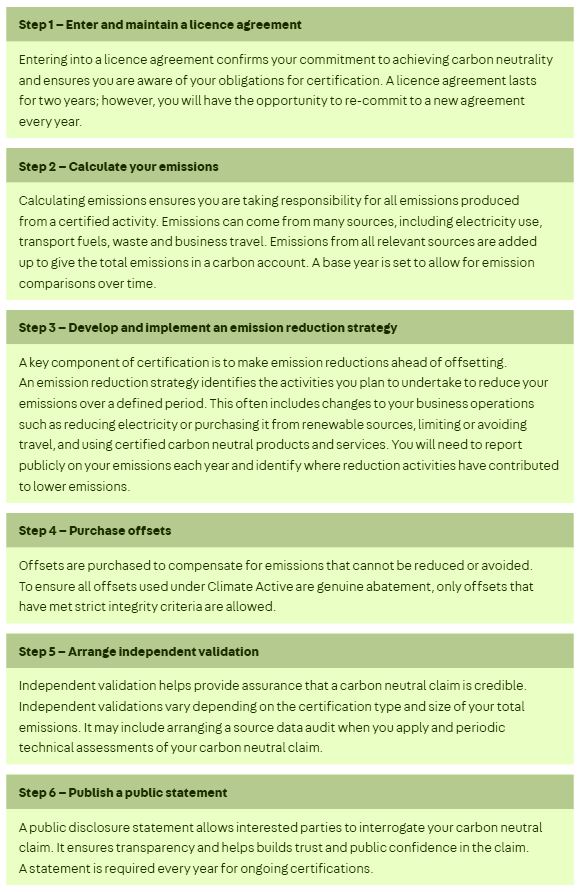

CARBON NEUTRAL CERTIFICATION

Once zero GHG emissions status has been achieved and is sustainable into the future, then an official certification can be sought through the Climate Active program (climateactive.org.au/be-climate-active/certification). To be certified carbon neutral, a business must not produce any excess GHG emissions and show this to be the case on an ongoing basis. Once certification has been achieved, if there are excess carbon credits generated by the business then consideration maybe made to sell those carbon credits through the Clean Energy Regulator, the independent statutory authority responsible for administering legislation aimed at reducing Australia’s carbon emissions and increase the use of clean energy (cleanenergyregulator.gov.au)

PLAYING THE MARKET — AUSTRALIAN CARBON CREDITS (ACCUS)

The Australian government has allocated funds for an emissions reduction fund which in the future will allow the trading of Australian Carbon Credits (ACCUs) which have been certified under the Clean Energy Regulator’s standards. This will allow carbon neutral businesses to on sell surplus ACCUs to industries that do not have the ability to decarbonise their businesses and have to purchase carbon credits to offset emissions to become carbon neutral. To generate ACCUs that are certified for trading is not a straightforward or easy process at present.

Winegrape growers might assume that because they have land and vegetation in their vineyards that they will automatically have ACCUs which they can turn into cash.

The prospect of making passive income from sequestering carbon and selling the credits is obviously appealing to vineyard landholders however, it is not a simple or inexpensive process. Firstly, the landholder must be certified carbon neutral under the Climate Active program guidelines. Only then can surplus carbon credits be traded. Landholders must also demonstrate that any carbon credits they generate are from a change in land use which for many farmers might not work and be counterproductive to their current agricultural production. Whilst the scheme doesn’t allow for existing permanent crops such as grapevines to be considered as ACCU generators in the scheme, it does allow for the midrow, headlands and land surrounding vineyards to be used to generate ACCUs.

A response to this aspect of the carbon economy has been the emergence of carbon ‘trading’ companies, also known as ‘aggregators’ or ‘project developers’. These companies facilitate the sale of your excess carbon credits (additionality) to the carbon economy where others purchase them to offset their own emissions in exchange for a commission of between 20-30%. It is a case of buyer beware when entering this carbon economy as project developers have various inclusions and exclusions as part of their commission. Keep in mind that carbon stability for offset ACCUs sold need to be audited regularly with associated costs of randomised soil sampling and laboratory analysis usually borne by the landholder which is not a cheap exercise. Aerial imagery has been touted as a quick fix for auditing soil and vegetation carbon levels from the air however, this is yet to be realised in practice and is still being developed.

The biggest single consideration to becoming a trader in the ACCU market is that the land and vegetation used has to be committed to carbon credit generation for more than 25 years with testing required every three to five years.

The acclaimed environmental scientist, author and explorer Tim Jarvis, through his Forktree project, is trialling methods on a property in the Fleurieu Peninsula, South Australia, for quantifying carbon stored in soil and vegetation (www.theforktreeproject.com).

It is hoped that the project will allow small to medium sized landholders to calculate more easily carbon sequestration rates and improve biodiversity at the same time.

For further information and the process and eligibility of a proposed ACCU project visit: https://www.cleanenergyregulator.gov.au/ERF/About-the-Emissions-Reduction-Fund/emissions-reduction-fund-schematic.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This is not my first attempt to write about this topic. Fifteen years ago I wrote a piece for Australian Viticulture (since incorporated into the Wine & Viticulture Journal) titled ‘Carbon neutral viticulture — the inconvenient truth’.

I even went as far as establishing a certified carbon neutral vineyard and used it as a case study. I remember there was a real buzz around that time, especially after the release of the documentary ‘An Inconvenient Truth’, presented by former US Vice President Al Gore. Then, all of a sudden, the momentum was lost and a hiatus set in for the next 15 years. Thankfully, it seems we are back where we started, only this time there is government support, new technology, a new generation at the helm and, finally, it seems, a greater social will to have a real crack at reducing GHG emissions.

REFERENCES

Hoare, T. (2008) Carbon neutral viticulture – the inconvenient truth. Australian Viticulture 12(2):39-42.

RESOURCES REFERRED TO IN THIS ARTICLE

A Guide to Carbon Footprint Assessment for South Australian Viticulture Production Systems https://agex.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/1327-Viticulture-producer-guide-FINAL_July22.pdf

A Guide to Greenhouse Gas Reduction for South Australian Grapegrowers & Winemakers https://agw.org.au/assets/environment-biosecurity/Greenhouse-Gas-Reduction-Guide-Nov-2010.pdf

Carbon Neutral Claims (Wine Australia) https://www.wineaustralia.com/getmedia/78afcedea124-4ec8-ac88-89bccb7ad61d/WA_Factsheet_ CarbonNeutralClaims_May-2021-pdf.pdf

Climate Active Guide https://www.climateactive.org.au/sites/default/files/2022-07/climate-active-guide.pdf

Australian Wine Carbon Calculator https://www.awri.com.au/industry_support/sustainable-winegrowing-australia/carbon-calculator/

Greenwashing by Businesses in Australia: Findings of the ACCC’s Internet Sweep of Environmental Claims https://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/GreenwashingbybusinessesinAustralia.pdf

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to Edward Scott, from Soil and Land Co. (soilandland.com.au/in-touch-with-your-soil.html#/) for his time and explanations of the complexities of the carbon economy for this article

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2023 issue of the Wine & Viticulture Journal. To find out more about our monthly magazine, or to subscribe, click here!