By Corrina Wright, Oliver’s Taranga, McLaren Vale, South Australia

First published in the March/April 2013 issue of the Wine & Viticulture Journal

The Oliver’s Taranga journey with Sagrantino began more than 10 years ago, when bright-eyed and bushy-tailed Mark Lloyd, from Coriole, and Chester Osborn, from d’Arenberg, spent a bit of time in Italy scoping out some varieties that may have potential in McLaren Vale. They were inspired to visit the home of Sagrantino, in Montefalco, Umbria, by the late great Greg Trott, of Wirra Wirra, after many evenings of pizza and Sagrantino di Montefalco at the iconic Russell’s pizzeria in Willunga.

Oh, to have been at those dinners! But I digress.

Although they enjoyed the wines they found in Montefalco immensely, Mark and Chester had both run out of plantable land at the time, so requested we plant some Sagrantino for them to purchase under contract. At the time, more than 60% of our 300-acre vineyard was planted to Shiraz, so Sagrantino was a significant departure from the norm, but an exciting journey to embark on.

The variety had been in Australia for a couple of years. The Chalmers family brought it in from Italy via their relationship with the Matura Group, and had planted it in their Euston vineyard on the New South Wales/Victorian border. There was very little information available on the variety due to its rarity, even in Italy. In Montefalco, it had been made into a sweet passito style wine used in religious ceremonies for centuries, but in 1992 was granted DOCG status as a dry red wine. This resulted in somewhat of a rebirth for the variety, of which only a small number of plantings remained. There is now thought to be close to 300 acres of Sagrantino vineyards in Montefalco, but they still only make up around 6% of the grape production of Umbria.

In 2004, after sourcing the vine cuttings from Chalmers Nurseries, we planted the first Sagrantino vines in our vineyard in McLaren Vale. They are grafted onto Paulsen rootstock and are the MAT 1 clone, as selected by the Matura Group. The soils the vines are planted on are very shallow, comprising low water-holding red brown earth over ironstone and limestone. The soils are quite tough, lacking nutrients, having traditionally being used as cropping land.

The vineyard was shallow ripped prior to planting with a 2m spacing between vines and 3.3m between rows. Each vine has two 2L drippers, and the vines were sprawled for a year, before establishing a single-wire, spur-pruned canopy. We largely based the vine structure on what has worked for Shiraz in our vineyard for years. Limited information was available on the establishment of Sagrantino at the time, so we ended up going with our gut feel.

We very quickly discovered that Sagrantino in our vineyard was very slow growing, had super short internodes and was generally extremely sluggish.

Perhaps planting the vines on one of our toughest soils wasn’t the best idea after all! The vines also turned out to be carrying a fairly high viral load. After two years trying to establish the vines with very slow results, Don (our viticulturist) travelled to Montefalco to meet with growers in the homeland of Sagrantino. He learned that they were generally pruning to only one bud, and the vines were planted at much higher densities than ours. When discussion turned to the sluggish growth, Don was informed by a number of growers to “just be patient!” While they acknowledged the impact of the virus, most informed him that the ‘clean’ stocks were not popular with the local winemakers at all, and warned against going down this path.

Eventually the vines established and produced their tiny first crop in 2007, giving solid results for both Coriole and d’Arenberg’s resultant wines. Unfortunately, the 16-day heatwave of 2008 resulted in the fruit cooking on the vine, and it was not picked. So, it wasn’t until 2009 that we had the chance to experiment with the variety again and, by this stage, we decided that Oliver’s Taranga would also have a crack at making a Sagrantino under our ‘small batch’ label.

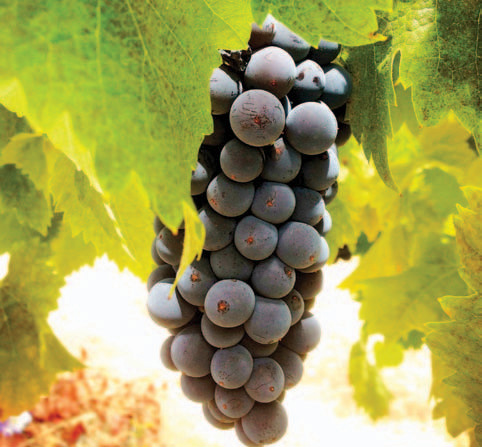

A typical bunch of Sagrantino is quite small, with very small, round, thick skinned berries that are compact within the bunch. They have the look of Cabernet berries, but more red-purple in colour, with a significant bloom on the skin. The growth of the vine is not vigourous, hence the canopy is quite sparse and tends towards yellow-green in colour. In autumn, the leaves are particularly spectacular, turning a vibrant, almost fluorescent red, and becoming the subject of many a painter’s brush or photographer’s lens! It is common to see numerous cars pulled over with people checking out the vineyard or setting up an easel.

Sagrantino tends to ripen relatively late in our region, after Cabernet Sauvignon, but before Petit Verdot. It doesn’t seem to be particularly susceptible to any of the mildews or botrytis, though the tightly packed bunches could cause havoc in very wet regions. The vines are relatively tolerant to heat (apart from 16-day heatwaves!), and don’t tend to drop leaf. In terms of water requirement, the vines seem to be similar to Cabernet Sauvignon, requiring slightly more than the hardy Shiraz.

The most striking thing about the Sagrantino grape is its extraordinary level of tannin in its skin and its high natural acidity. This is truly challenging to get your head around when you first taste the variety on the vine. It is this high tannin, high acid character that drives the choices when turning the fruit into wine.

Now heading towards our sixth vintage with Sagrantino, we have worked on a number of trials in the winery. Everything from traditional fermentation, to significant extended skin contact, and many things in-between. We are now feeling a little more confident with the management of the tannins, and have come to a happy place by splitting the ferment. One portion of Sagrantino is processed using heading down boards and not much cap movement in an indigenous yeast ferment. We then press off using a basket press at around 1o Baume, popping the wine straight into old, large format oak. The other portion is left on skins for around 40 days before pressing. The tannins in the extended skin contact parcel start to gain in generosity, becoming like a rich 70% cocoa chocolate. Meanwhile, the pressed off early portion has more apparent tannins, but the beautiful violet, floral fragrance is maintained. We don’t add any tannin or acid to the ferment, and just let it do its own thing – it is a pretty hands-off kind of wine! It does need some time in barrel to allow the tannins to develop. In Montefalco, there is a minimum ageing required to meet the DOCG regulations of 30 months, and the wines have been known to age for decades. If you would like to experience some of the ‘real’ thing, I highly recommend wines by Arnaldo Caprai or Paolo Bea.

It has been very interesting introducing customers to this wine in our cellar door and via our distribution networks. There has been significant interest from the trade, especially in restaurants and high-end specialist bottle shops. The tannin structure of Sagrantino screams out for food. Even when we are out on the road tasting with restaurant and wine shop buyers, we make sure to bring some slices of prosciutto or salami, and encourage them to try the wine with and without food.

Sagrantino is currently very much a hand sell, but we still believe that the potential is there to produce an exciting wine, and will continue to produce small volumes under our ‘small batch’ range into the future.

Sagrantino

By Peter Dry, Emeritus Fellow, The Australian Wine Research Institute

Background

Sagrantino (SAH-grahn-TEE-noh) is a very minor variety in Italy that was rescued from extinction in the 1960s. It is grown in a very small area, around Perugia (Umbria), to produce Montefalco Sagrantino (granted DOCG status in 1992). Globally there were 995 ha in 2010 (up 154% from 2000), close to 100% in Italy. It makes up 7% of the planted area of Umbria. Sagrantino has been known since the late 19th century in Montefalco but does not appear to have spread elsewhere in Italy. The fact that it has very few synonyms (Sagrantino di Montefalco, Sagrantino Rosso) is perhaps indicative of its restricted range in Europe. It is said to have been introduced from Greece in the Middle Ages—but there is no DNA data yet to support this proposition. Historically it was used to produce a sweet wine from partially-dried grapes. Today Sangrantino is most likely to be used for varietal red wine—but may be blended with Sangiovese in Montefalco and surrounding communes. It was imported to Australia by Chalmers Nursery in 1998; there are currently at least 20 wine producers, mainly in SA (12 ha) and Vic..There is also a small area in California.

Viticulture

Budburst is mid-season and ripening is mid to late (about one week later than Shiraz at Swan Hill). Bunches are small to medium, loose to well-filled (with some clonal variation for the latter). Berries are medium, dark-blue or black with thick skin. Vigour is low and growth habit is semi-erect. Yield is said to be low and variable in Italy but moderate yields can be achieved with irrigation in Australia. It is adapted to a hot dry climate and has stood up very well to heat waves in inland regions in Australia. It also has good tolerance of spring frosts. Bud fertility is good and spur pruning is most common. Harvest can be fully mechanized but low shaker speed is required because canes are brittle. It has moderate tolerance of powdery mildew and Botrytis, but not downy mildew.

Wine

Very high juice polyphenolics results in wines with good structure, high in colour and tannins. Wines are fruity with a good body and acidity and delicately perfumed. Descriptors include forest fruits, cherries, mulberries, violets and vanilla. Ageing potential is very good. Long maceration, e.g. 4-5 weeks, with gentle cap management may be used in Italy.