By Brad Hickey, Brash Higgins Wine Co., McLaren Vale, South Australia

First published in the November/December 2012 issue of the Wine & Viticulture Journal

McLaren Vale-based Nero d’Avola producer Brad Hickey travelled to Sicily, in Italy, in 2011 to investigate local growing and vinification of the variety. In addition to collecting ideas about how to maximise Nero d’Avola’s potential on home soil, Brad was inspired to use amphorae as a winemaking technique.

When I moved to McLaren Vale six years ago, after a decade spent buying wine for restaurants in New York City, I started thinking about new varieties we could plant on our vineyard that would not only thrive in McLaren Vale, but make for interesting drinking as well. The drought years had been making life hard, even for our Shiraz and Cabernet Sauvignon plantings, and we felt we needed to find some better suited grapes to bring onboard. Nero d’Avola fitted the bill.

When I moved to McLaren Vale six years ago, after a decade spent buying wine for restaurants in New York City, I started thinking about new varieties we could plant on our vineyard that would not only thrive in McLaren Vale, but make for interesting drinking as well. The drought years had been making life hard, even for our Shiraz and Cabernet Sauvignon plantings, and we felt we needed to find some better suited grapes to bring onboard. Nero d’Avola fitted the bill.

In 2009, Brash Higgins obtained some of the first cuttings of the Sicilian red winegrape Nero d’Avola available in Australia from Binjara Vine Nursery (formerly Chalmers Nursery), in Euston, New South Wales. Nero d’Avola is drought and heat tolerant to a certain degree, ripens late and thrives in its native Mediterranean climate, so it seemed like a good fit for coastal McLaren Vale and our evermounting heat and water issues.

Viticulture

2009-2010

In October 2009, we dedicated a half hectare research block on our Omensetter Vineyard to Nero d’Avola. Soils in this block are relatively shallow (40-50cm) red brown clay loam over a deep, soft marl limestone. In the winter of 2009, we asked Dr Nuredin Habili, of Plant Diagnostics, at the Waite campus of The University of Adelaide, to perform a virus test on our Shiraz rootstock, which was planted in 1997. The results came back affirmative to graft Nero d’Avola. Field grafting was conducted later, using two buds per vine on the Matura 1 clone from the Matura Group, in Italy. The clones grew exceptionally well, exhibiting great vigour and not needing any irrigation until the first week of December, followed by small amounts on a regular basis until mid-February. Vines were trained on a single cordon trellis, and the cordon was filled by February 2010. We noted that foliage was prone to powdery mildew.

2010-11

The first fruit bearing year, we pruned the lateral growth hard from the main cordon back to basal buds. Vines grew strongly, with many double buds providing two shoots per node. These were shoot-thinned back to one shoot per node. A lazy ballerina trellising system was used, although this may have contributed too much shading in such a cool and wet season. We double bunch thinned what was a potentially immense crop down to 10 tonnes per hectare. No irrigation was necessary until the beginning of February, and only 0.4mL per hectare was applied all year. A minor bit of sun scorch was also noted on leaf tissue during a particularly hot weekend of 40°C in late January.

Diseases became entrenched with heavier rains and it became obvious to us that Nero d’Avola was prone to powdery and downy mildews, as well as botrytis. These conditions of disease pressure were exacerbated by the wetness of the vintage. All diseased bunches were removed leading up to harvest on 1 May, with regular leaf plucking to open up the canopy. Baume levels thankfully accelerated from 12.5 to a ripeness of 13.5 during two weeks of warm, dry weather at the end of April. The block was handpicked in three hours, and roughly two tonnes of healthy fruit was collected.

It was not exactly a Mediterranean-style vintage, but we got the fruit ripe with a lot of hard work and a little luck, and just in the nick of time, too, before the even heavier winter rains came.

We did employ a VSP trellis the following year, which offered much better protection from botrytis. The 2012 vintage was a much easier and healthier vintage than 2011, with only powdery mildew becoming difficult to control. The harvest came in almost six weeks earlier as well.

Sicily visit

During the past few years, I have been drinking wines from Sicily, the second largest wine region in Italy. However, once we safely grafted the Nero d’Avola material to our Omensetter Vineyard, I knew we had to visit. I travelled to Sicily in August 2011 for three weeks with my viticulturist Peter Bolte (a key contributor to this article), and my partner Nicole Thorpe to see how the Nero d’Avola vines coped during the hottest time of the year. Ironically, compared with the wet 2011 season in McLaren Vale, the 2011 vintage in Sicily turned out to be its hottest and driest in 40 years.

We stayed at COS Winery, in Vittoria, one of the leading wineries in Sicily, and a major high end Nero d’Avola grower and producer. Today, COS has expanded significantly from its humble origins in the 1980s and now produces approximately 160,000 bottles per year using biodynamic viticulture methods. After touring the COS vineyards and cellars with its talented chef and vigneron Pino Guerrisi, we observed the soils to be almost identical to our Omensetter Vineyard, half a metre of red clay over limestone, reaffirming our belief in the variety’s compatibility to our geology in McLaren Vale. We also noticed relatively thick residues of sulfur and copper on the vines, as well as evidence of downy mildew, which is interesting since it was such a hot, dry growing season. Most of the vineyards were weed free, which seemed unusual for biodynamic farming. Irrigation was only added six weeks prior to harvest.

COS’s range of Nero d’Avola wines are typically perfumed with sweet cherries and a subtle herbaceousness. The palate is fresh and pure with sweet, rounded fruit and a lovely, fresh, spicy cherry character; expressive drinking and a style we wanted to try to emulate in McLaren Vale. For more details, I highly recommend Robert Camuto’s excellent book on Sicilian wine and the people behind it, Palmento: A Sicilian Wine Odyssey.

Amphora

One of the most significant ways to affect the taste of the juice after harvest is the vessel in which the wine ferments and ages. COS, and another provocative winemaker we visited in Sicily, Frank Cornelissen, are also famous for using 400-litre clay amphorae, sunk into the ground, for some of their red and white wine fermentations.

COS’s Nero d’Avola-dominant ‘Pithos’, and Cornelissen’s ‘Munjabel’ wines from Etna, using Nerello Mascalese, are made using this ancient technique. Both wines had superb mineral depth and intense aromatics. I found this fascinating and wanted to try the same back in Australia. After a long search, we had five 200L clay amphora vessels made for us by skilled Adelaide potter, John Bennett, using clays from a local quarry almost identical to our vineyard’s soil. The pots were coated internally with bee’s wax as they came out of the kiln.

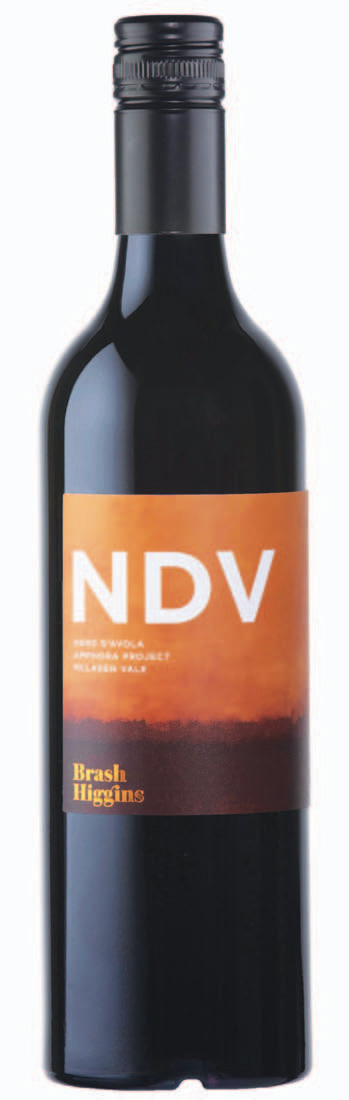

At harvest, we destemmed the Nero d’Avola grapes and left the juice to undergo a wild ferment on its skins and lees. Once the skins sank and the ferments went dry, we sealed the amphorae for seven months, covered airtight with stainless steel lids. The idea was to extract as much flavour as possible from the grapes and to provide additional layers of complexity. We basket pressed the wine off skins 210 days later at the end of November, primarily because I could not wait any longer! We let the juice settle naturally and the wine was bottled before Christmas. We produced 112 cases of 2011 Brash Higgins Nero d’Avola, which tasted promising, full of intense savoury aromatics, like its Sicilian brethren, loads of wild cherries and a mouthwatering acidity, but also with all the orange and lavender aromas that our terroir seems to produce.

Amphora seemed like a good way to not only introduce Nero d’Avola to Australia, a high acid and transparent varietal, but to make a statement. Also, we were just as ready as the Italians to step deep into the past to make a leap forward. I have found amphora wines diabolical, challenging, sometimes ethereal, sometimes scary, but always thought-provoking wines that reflect, as close as possible, the true terroir of the vineyard.

Conclusion

Nero d’Avola is prone to diseases, primarily powdery mildew, but also botrytis in wetter seasons. It appears to be quite a vigorous and heavy cropping variety when it has access to an abundance of readily available water. Our observations of Nero d’Avola’s growth habit, vigour and ripening suggest planting should be considered primarily on relatively bare and shallow like those soils situated in the earlier ripening sub-regions of McLaren Vale. Cultural methods certainly need to be employed to be successful in obtaining a crop of healthy, good quality fruit. Heavy pruning, appropriate trellising, bunch and shoot thinning and leaf plucking will all need to be considered and certainly conducted in vigorous growing seasons.

Nero d’Avola is capable of producing complex wine in a number of styles, and is a prolific producer if yields are not kept in check. Although it is said to be similar to Shiraz, it differs in that it has dustier tannins, higher natural acidity, more savoury elements, and ripens significantly later; all points that can lead to some distinctive flavours and new flavour profiles for the Australian palate.

NERO D’AVOLA

By Peter Dry, Emeritus Fellow, The Australian Wine Research Institute

Background

Nero d’Avola (nero DAHVOLLAH) is widely grown in Sicily, particularly in the provinces of Agrigento, Siracusa, Caltanissetta and Ragusa. It is also grown to lesser extent in Calabria where it is known as Calabrese. The variety has been grown for centuries in Sicily and is presumed to have originated from close to the town of Avola in the south-east of the island. In recent decades its wines have become more reputed, to such an extent that the Italian Wine and Food society has now included it in their top twelve red wine varieties of Italy. Nero d’Avola is the principal variety of the only DOCG wine of Sicily, Cerasuolo di Vittoria, for which it must be 60% of the blend with Frappato. Globally there were 16596 ha in 2010 (up 43% from 2000), close to 100% in Italy. Nero d’Avola makes up 15% of the planted area of Sicily. Synonyms include Cappuciu nero, Calabrese d’Avola, Calabrese de Calabria, Calabrese di Noto, Calabrese Dolce, Calabrese nero, Calabrese Pittatello, Calabrese Pizuto, Calabrese Pizzutello, Calabrese Pizzuto, Calabrisi d’Avola and Fekete Calabriai. In Australia there are currently at least 36 wine producers, mainly in warm to hot climatic regions in SA (21 producers), Vic. and NSW. In 2015, there were 115 ha in Australia (28 ha in SA).

Viticulture

Budburst and maturity are mid-season (approximately two weeks after Chardonnay in Sicily). Vines are very vigorous. Bunches are well-filled to compact, moderate to large, and yield is moderate to high. In Sicily where irrigation is permitted, a good yield is considered to be 9 t/ha. Berries are purplish-black, small to medium. It performs well in a hot, dry climate and has been successful with 1103 Paulsen as a rootstock in Sicily (140 Ruggeri can induce excessive vigour). Traditionally grown as bush vines, Nero d’Avola is now more likely to be trellised. Although spur pruning is often used, basal bud fertility is not high so cane pruning may also be used. It is susceptible to powdery and downy mildews.

Wine

In Sicily, Nero d’Avola is used as a component in blends and for varietal wines, from light easy drinking styles to big, full-bodied reds. It blends well with other varieties, e.g. indigenous such as Frappato and Nerello Mascalese, or introduced such as Merlot. Wines are well coloured, medium- to full-bodied with good acidity and tannins and velvety, smooth taste. Flavour descriptors include plum jam, dark cherry, raspberry, hazelnut, fresh herbs, spicy and chocolate. It has been likened to full-bodied Australian Shiraz.