Matter other than grapes, known by the industry as MOG, presents a logistics challenge with its separation from the yield and, ultimately, its disposal. Ongoing trials across some of Australia’s wine regions, including Padthaway and the Barossa are determining the effectiveness of MOG-sorter technology, and deciding their viability in the industry. Journalist Samuel Squire reports.

Harvesting technology has changed drastically over the last half-century, and with a new generation of mechanical harvesters roaming the nation’s vineyards, more ways of countering common harvesting issues are being developed.

One such common issue that producers face at harvest time is MOG (matter other than grapes). Mechanical harvesters are great at their job, but the challenge of separating what is and isn’t needed from the final bin can be a challenge.

Wine Australia’s Agtech Program manager Dave Gerner is at the forefront of the management of MOG and is working collaboratively with industry on emerging new technologies.

He said while the upside of mechanical harvesting has far outweighed the unwanted by-product of MOG in the supply chain, the impact of MOG remains a significant challenge.

“Many of the larger companies would have different perspectives on the cost and imposition of MOG in their supply chain, and there is still a diversity of opinion as to who pays for this,” Gerner said.

“For example, the cost of transporting fruit containing MOG from the vineyard to the winery – and then the need to remove that MOG at the winery – is largely unmeasured as a sector.”

Reducing, or potentially removing, MOG from grape harvests will inevitably clean up the supply chain for producers and could ultimately lead to reduced costs to the winery for removing MOG, and ultimately will make winemaking a little more efficient.

The main advantages of MOG-free harvests are threefold: wine quality and stylistic uplift, reduced costs in transporting MOG to and from the winery, and winery throughput optimisation.

“Then you have the consideration of the cost of production and related efficiencies at the winery, as MOG creates bottlenecks at the crushers as production systems slow down to accommodate destemming and sorting,” Gerner said.

“These breakdowns and mechanical failures are frequent and expensive.”

The challenge for many producers, including the larger vertically integrated wine companies, is understanding who in the supply chain pays for this capability. On board selective harvesters are expensive, although many contractors and third-party harvesting services now offer these units as part of their fleet capability.

Gerner is adamant that it is no secret that MOG-free harvests lead to wines that are “brighter, have better colour and provide winemakers with more flexibility to create the wines they desire. There is significant research to suggest that MOG-free harvests enable flexibility with winemaking, such as allowing for brighter styles and colours”.

Gerner adds that selective harvesting reduces berry maceration, which slows down the onset of biochemical reactions pre-fermentation and puts a greater degree of processing and winemaking choices back in the hands of a winemaker.

New solution trialled

While research for methods of reducing MOG in harvests is going full steam ahead, one supplier has partnered with Wine Australia to supply its new solution for the trials.

Aussie Wine Group (AWG), a supplier to the wine industry, has recently developed sorting technology that allows for the on-the-go removal of MOG, whether by sorting trailer equipment, harvester boom-mounted sorters, in-harvester sorters or high-capacity trailing sorters.

Trials of AWG’s standalone products were recently conducted in some of South Australia’s most iconic wine regions. The trials, which are still ongoing, are a part of Wine Australia’s AgTech Program aimed at implementing more beneficial technology into the wine sector.

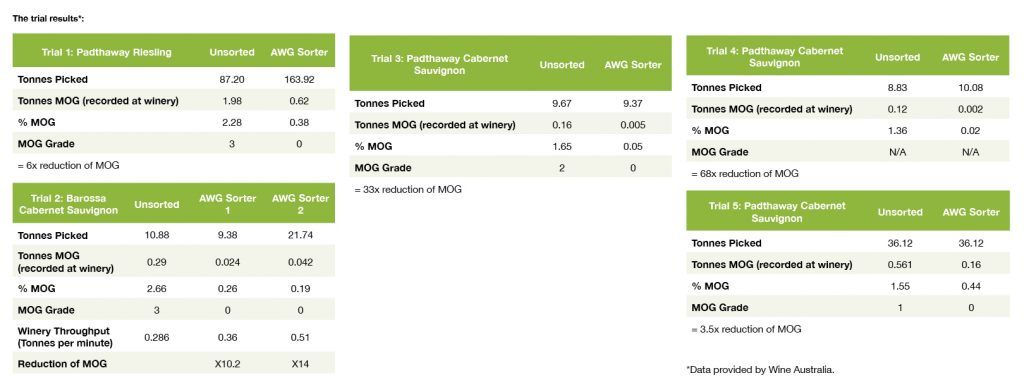

Five trials have been conducted so far, and on all counts, the tonnage of MOG recorded at the winery post-harvest, on each trial, was significantly less than with unsorted yields.

The trials were conducted completely independently of Aussie Wine Group, which only supplied the technology for use, as a way to prove to producers that a viable solution to reducing MOG is available.

AWG managing director Malcolm Villis says the company’s developed MOG sorter technologies are able to provide yields with significantly less MOG present and not impacting on harvest times.

“The AWG Infield Sorter has been developed over the last seven years with testing and trials in the US and throughout the Australian wine industry,” he said.

“The unit consistently delivers MOG levels of 0.02-0.4% with yields as high as 40+ tonnes an hour, or as fast as the harvester can pick regardless of the make of harvester.

“The unit has a three-tier sorting system allowing full berries to fall directly to the catching system below, hence maceration of the berries doesn’t allow full berries to be delivered to the winery.

“All MOG is left in the vineyard allowing winery intake efficiencies to be increase by 23% on a standard MOG one load of fruit.”

The five completed MOG sorter unit trials were independently conducted by Wine Australia last season and were carried out in the Barossa, Langhorne Creek, McLaren Vale, Padthaway, and Coonawarra wine regions. Currently, results of the Barossa and Padthaway trials have been released.

Villis says AWG received testimonials from some of the producers involved in the trials gave positive feedback.

“A vineyard in Langhorne Creek said using the AWG Infield Sorter allowed them to lower harvester fan speeds and gain weight and full berries at the vineyard and deliver zero MOG every time,” he said.

“A vineyard in Padthaway said the AWG units were easy to use and saved time during harvesting operations, delivering zero MOG.”

The trials, Villis said, gave AWG the responsibility of supplying the units, while carrying out operator and safety training.

During the trials, every second vine row was harvested under normal operational procedures, while the other rows were harvested using AWG’s MOG sorter technology.

At the wineries, MOG was weighed out of the destemmer and the destemmer processing times were also measured.

On determination of the trials proved that AWG’s full range of premium MOG sorter units can handle up to 20 tonnes an hour, while the company’s high volume units can process over 40 tonnes an hour.

Villis says these units are also able to be retrofitted to most existing harvesters, harvester boom arms, and on the top of trailer bins, all while not slowing down harvest times.

Case study: a spotlight on MOG at the weighbridge

Multispectral imaging is capable of discriminating MOG (material other than grapes) and Botrytis-infected grapes in samples from mechanically harvested grape loads, a recently completed Wine Australia funded study has found.

The findings are important, because being able to identify and manage contaminants and MOG at the weighbridge is a critical step in managing overall fruit quality and wine.

“Leaves and petioles collected as part of grape harvest and disease-affected fruit have the potential to impact on wine quality when they are included in the ferment,” said principal investigator Dr Paul Petrie, who undertook the research while at the Australian Wine Research Institute (AWRI).

“High MOG levels can lead to undesirable impacts on wine flavour and aroma. Disease, especially Botrytis, contains enzymes that can lead to rapid oxidation of the juice and wine – markedly reducing its quality and turning the wine brown.”

Currently, MOG within mechanically harvested fruit is assessed using a visual rating system “so there is always room for conjecture around the accuracy of the MOG assessment”, according to Dr Petrie.

While chemical analysis methods have been trialled to quantify the level of Botrytis in fruit, Dr Petrie says these methods are often not precise at the low concentrations where Botrytis can have an effect, and samples take some time to be collected and analysed.

“The imaging system we have developed, however, helps to overcome these issues – with the added benefit of rapid assessment and analysis,” Dr Petrie said.

The team initially used hyperspectral imaging with a full spectral linescan camera to assess both laboratory-infected Botrytis samples and field samples.

Eight wavelengths were then selected for use with a filter-based multispectral camera. This system was selected because it was more applicable for use at the winery weighbridge.

What the research team found was encouraging: spectral imaging was not only able to identify Botrytis infection and MOG, but could also differentiate types of fungal infection, along with grape sunburn and shrivel.

The study found:

– Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) could discriminate between clean and infected red and white grapes. The calibrations worked across growing regions, grape varieties and Botrytis sources.

– The multispectral camera system was able to quantify the amount of MOG and Botrytis-affected fruit that was added to samples collected at the weighbridge. This proof of concept supports the development of commercial systems to monitor loads when they are delivered to the winery.

– HSI could also discriminate Botrytis infection from sour rot (mixed fungal and bacterial infection of grapes). Washing sporulating berries with grape juice or smashing berries, to simulate mechanical harvesting, did not prevent identification of Botrytis.

– HSI could identify sunburn in white grapes and shrivel in red and white grapes; and discriminate other grapevine components that often form MOG in mechanically harvested grape loads (i.e. canes, wood, petioles, leaves and insects).

“The findings are exciting, because having an objective system to measure Botrytis bunch rot and MOG will provide greater transparency of the assessment process and help prevent the production of poor quality wine,” said Dr Petrie.

This project was funded by the Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment as part of its Rural R&D for Profit program and Wine Australia, in partnership with the AWRI.

– This study was published by Wine Australia and is republished here with permission.

.

This article was originally featured in the October 2021 issue of the Grapegrower & Winemaker magazine.

To read more articles like this, subscribe online here.