A comprehensive guide to alternative energy options for winemakers

Power bills are rarely a pleasant experience for most business operators, and understanding what they mean can also be a challenge. From one vintage to the next, prices can soar ever higher with little explanation. That’s why Chloe Szentpeteri spoke to experts in energy, engineering and winemaking to put you on the path to better energy efficiency.

Electricity has been identified as the single largest cost factor for many winemaking businesses.

There are many options that help reduce power costs, and most of them start with a few small steps that cost very little, but will save significant dollars.

Understanding power usage patterns can be the first major step for operators to gain insight into how energy efficient their operation is, and at what cost to their business.

There are two sides to the equation: consumption and the rate at which a business pays.

Firstly, consumption can be determined by the actions wineries take to reduce the amount of power used by applying various techniques to become more efficient.

Secondly, the rate at which businesses are charged for energy can be negotiated resulting in an agreed contract between them and power suppliers.

There are a number of measures that can be taken to reduce this rate, which will be explored in greater detail later.

But let’s begin with consumption. The key areas to focus on include refrigeration, pumping, compressors and lighting.

Refrigeration

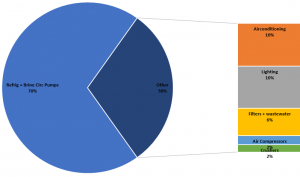

South Australian Wine Industry Association’s (SAWIA) environmental project officer, Mark Gishen, said that refrigeration consumes between 50-70% of electricity used at a typical winery (see Figure 1).

Gishen is a seasoned consultant and manager of operations and projects for the wine industry, and is an expert in associated technology. He has more than eight years in his role at SAWIA and 11 in his personal business, Gishen Consulting.

He said the equipment used for refrigeration, such as compressors at a refrigeration plant, should be run as efficiently as possible. This can be done by upgrading or optimising the performance and operation of the machinery.

While upgrading comes at a small sum in the short term, the financial savings far outweigh this when looking at the improved long-term performance and energy savings.

“If you want to reduce your actual consumption there are also other ways,” said Gishen. “For example, [by] not unnecessarily overcooling when you don’t need to.”

He said tanks that don’t require constant refrigeration should not be kept excessively cold and should be turned off when not in use.

Gishen said turning tanks off is a bit like turning off the lights when you leave the room.

“Turn switches off and turn cooling off when you don’t need it rather than running the whole thing all the time at a set point and forgetting about it,” he said.

Running the refrigeration system at a slightly higher temperature can also save hundreds, if not thousands of dollars, from your energy bill.

“If you push the set point up by one degree you can save several per cent [in consumption] very easily and that’s unlikely to cause any harm to your wine quality,” Gishen explained.

Temperature and cold stabilisation

Yalumba’s executive director, Andrew Murphy, and winery operations manager, John Ide, are two experts in the field of winery engineering and both have effectively managed energy efficiency at the winery’s Angaston operations in the Barossa.

Both agreed that refrigeration is the first point of power saving.

By using the above steps and adjusting temperature on tanks accordingly, the winery has had conservable success in becoming more efficient with power usage.

“So with electrical application it’s all about heat transfer. It’s not about cold, it’s about lack of heat,” Murphy said.

In simple terms, refrigeration is taking heat out of something and removing it through a condenser.

“We have a little bit of brine for a few applications in sparkling wine production for some pressure tanks, but primarily we’re directing expansion of ammonia or chilled water for our fermentation.”

“So if you get red ferment that you run between 18°C and 26°C you don’t need -10°C in a refrigerant to get that, you just need a temperature differential to shift it so that’s why we use water and +4 as a primary refrigerant,” Murphy said.

“And when you’re running at those high temperatures your fridge runs much more efficiently. The amount of power you put in, the higher [the] heat transfer.”

Ide explained that cold stabilisation is run at about two to four degrees to recover potassium bio tartrate and is then seeded in large amounts.

“Other people would typically seed it at very small amounts because it’s quite expensive, and then not recover it and run at maybe -4°C, whereas we can get the same effect at 2°C over 24 hours really.

“We can achieve that because we recover all the tartrate and then reuse, so then we can dose in very large amounts compared to what other people do,” he said.

Pumping and compressors

On average, pumping can use up between ten and 20%, and compressed air between five and ten per cent, of the total amount of power used by wineries.

To be more cost effective, Yalumba pumps ammonia around its site as the primary refrigerant for chilling must and fermentation tanks.

The use of brine as a secondary refrigerant has also proven effective, in contrast to its costly and inefficient use as a primary refrigerant.

“Both our wineries actually work on pumping out primary refrigeration and using compressors. So instead of having 30, 40 or 50KW pumps, sending thousands and thousands of litres of brine around, we have 5KW pumps pumping hundreds of litres,” Murphy said.

“There are only two pumps to do the whole winery, very small because it works on pressure as well as pumping,” Ide added.

This refrigeration system also has the option of off-peak loading to reduce costs and power consumption by maximising compressor efficiency.

Another method of power saving is using variable speed drives on compressors, although it comes at a substantial initial cost.

A variable speed driver for a 450KW motor, for example, can be purchased for around $120,000.

But this outlay is likely to provide long-term benefits by cutting power consumption for many processes.

These can be applied not just to air compressors for refrigeration, but also for bottling lines and even air conditioning systems within office spaces.

Ide said a 20-30% reduction in power usage can be achieved by installing variable speed drives, with the possibility that larger-scale wineries could produce even better results.

LED lights

Lighting isn’t as big a concern as the other factors when it comes to the winery power bill.

On average, it takes up around five per cent of total energy used. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t ways to reduce costs by adopting more efficient options.

Although the price per unit of LED bulbs is expensive, they are a viable choice for winemakers leaving lights on 24 hours a day, and the return rate is quick.

“LED lights are typically less than two years payback for most areas, especially in wineries when you have lights on all night over vintage. Look at reduction and use,” Ide said.

Tariffs and demand

Apart from alternative choices to improve energy efficiency, savings can also be found by using a different approach to power rates, network tariffs and demand.

Tariffs are the pricing structure used by retailers for charging customers and these vary depending on demand.

There is a small selection of tariffs related to demand that should be considered, but there are many more when it comes to managing the amount of kilowatts used per cents, and per hour.

Retailers, such as SA Power Networks, buy electricity from the gas plant and then they sell electricity back to consumers.

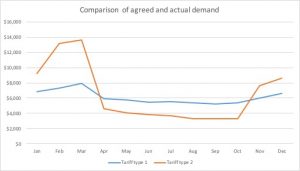

In South Australia there are two low voltage (LV) demand tariffs – agreed and actual.

LV agreed demand tariffs charge on the basis of a business’ highest demand during peak usage times during workdays and these come in two periods:

Annual Demand Period – Any half hour period between 12 noon and 9pm (local time) on workdays between November and March, excluding public holidays.

Anytime Demand Period – Any half hour period outside the annual demand period.

LV actual demand tariffs charge on the basis of a business’ maximum actual recorded demand during peak usage times on workdays and also come in two periods:

Peak Monthly Demand – Any half hour period from 12pm to 9pm, Monday to Friday.

Off-peak Demand Period – Any half hour period outside the peak period.

James McIntyre, an associate from energy consultants 2XE, has a thorough understanding of the field of energy efficiency, with a particular focus on power consumption and how to reduce costs in the wine industry.

According to McIntyre, energy providers use fundamental economics to balance out energy use by consumers.

“Because if they end up with massive peaks on electricity then that kills the grid. And that’s why the Tesla battery [in SA] is there because it helps alleviate that.

These peaks are also the result of demand. For example, during the middle of a heatwave, when consumers arrive home from work, the first thing many do is switch on the air conditions, like most other consumers.

Because of the spike in energy use, consumers are charged a premium for demand.

Figure 3 represents a full day’s energy consumption for two different wineries.

It shows how much power is used per hour, and the average amount used over two and three month periods.

The first winery (in black) has systems in place to ensure a consistent power consumption, unlike the second winery (in orange), which will be charged more for demand during the peak hours of a typical nine to five weekday.

“If you have a winery using an amount of electricity over a lengthy period, compared to a winery that uses all their electricity in one hour, [the latter] are paying so much more in demand,” said McIntyre.

“There’s about three times’ difference in price with peak and off-peak usage.”

This is where vintage impacts your energy bill. With a demand based tariff on an annual contract, users will be charged at the highest peak of energy consumption, even if it only hits that peak once in the entire year.

Automated systems

Systems should be operated wisely across the other months of the year and ‘smarter’ energy use during vintage will potentially save many thousands of dollars.

“Understand your energy use onsite and run your refrigerator off-peak as much as you can. To do that, effectively get rid of human error by putting an automated system on it and set it up like that,” McIntyre said.

“That’s one of the big ones because nobody is going to switch on their refrigeration system at 9pm at night and then come in at 6am because nobody is going to be there at that time.

“There’s no point in trying to chill 100 tanks at the same time. Chill a batch of ten then an hour later switch those off and switch on the next batch of ten.

“I have examples where wineries have saved around $200,000 just by changing the set point temperature by one or two degrees,” he said.

Another simple money saver is automating lights to switch off when business hours are finished, and switch on just before opening, to allow time for certain types of bulbs to heat up in larger scale operations.

Energy efficiency is no easy topic to navigate when there is an abundance of options that will help reduce power costs.

By understanding energy usage and the fundamentals behind energy contracts and bills, winery operators can place themselves in better stead to save money and optimise workplace performance.

Operators are encouraged to start with the basics and do simple research to decide what measures will work best for their individual needs.

For help with finding the best energy contract, or to gain a more thorough understanding of how to monitor energy, call your supplier or access SAWIA’s Wine Energy Saver Toolkit via http://www.winesa.asn.au/members/advice-information/environment/energy-efficiency/winery-energy-saver-toolkit/.

This article was originally published in the Australian and New Zealand Grapegrower & Winemaker, March 2018 edition.