High natural acidity in wine is something typical of the Italian red powerhouses Barbera, Nero d’Avola, Nebbiolo and Sangiovese. Journalist Samuel Squire dives into some of the history of one of Italy’s most-planted winegrape varieties, and speaks to Australian producers and an importer of Italian Barbera wine to find out where it stands in the local market.

In Italy’s Piedmont, Barbera is the most planted grape variety, accounting for three times the acreage planted to Nebbiolo. The variety is quite versatile and can be used in more than just single varietal wines, which is the reason it is so widely planted in its Italian homeland.

Ampelographers and historians who have written on the variety have largely determined its true origins, but nothing can definitively be said about its true age. Based on 13th century scripture (Italian Wine Connection 2018), Barbera originates in the hills of Monferrato in central Piedmont.

Before Italy’s Renaissance, Barbera wine was known as the “people’s wine” (Sweet 2018) and had been described as a commoner moving up in the ranks. It was known to be served at the tables of royals and curial in important cities.

According to University of California, Davis FPS historian Nancy L. Sweet, it was custom for Italian families in the Piedmont region to take their names from common or widely planted grapevines, botanical sources, or from different types of agricultural activities.

Sweet suggests there is also a historical connection between the Italian family names ‘Barbieri’, ‘Barbero’ and ‘Barberis’ to the vines of the region.

In 1909, French ampelographer Pierre Viala proposed the Oltrepò Pavese region as Barbera’s original home in his work Ampélographie (Sweet 2018).

Sweet states the name Oltrepò Pavese means “Pavia across the Po [River]” and refers to an area bordering Piemonte in the Province of Pavia to the south of the Po River, which was once a part of Piedmont.

Barbera is a very adaptable variety, too. It can grow in many different climates and soil types. It grows nowadays in the US and Argentina due to large-scale Italian migration.

Barboursville Vineyards near Charlottesville in the American state of Virginia first planted its Barbera in 1976 and made its first Barbera varietal wine in 1991.

Barbera’s name – or its origins – have yet to be fully agreed upon by today’s ampelographers. Compared to the agricultural writers of old, today’s ampelographers are more hyper-corrective about a grape variety’s name and origins.

Agricultural writers were not known to record the individual names of winegrapes on a wide scale until the latter half of the 19th century.

Even with a recorded history spanning back to 13th century Italy, Barbera’s written name wasn’t really used until the 18th century, according to one of the world’s leading experts in Italian wine, Ian D’Agata, author of Native Wine Grapes of Italy, published in 2014.

In his book, D’Agata stated, “The origin of its name is unclear; Pietro Ratti of Renato Ratti feels it’s a derivation of barbaro (barbarian) due to its deep red colour, while others believe the origin is vinum berberis, an astringent, acidic, and deeply hued medieval drink. Vinum berberis is different from the vitibus berbexinis referred to in a 1249 document located in the archives of Casale Monferrato, which was most likely another variety, Barbesino or Berbesino, better known today as Grignolino”.

Barbera is one of Italy’s top five most-planted native winegrape varieties, the third most common red grape and it is also one of the 15 most-planted grape varieties in the world, according to D’Agata’s 2014 research.

D’Agata also mentioned that Barbera has no long or distinguished history, continuing that most Italian wine exports believe it to be originally from Monferrato, and not from the neighbouring regions of Alba or Asti. Many others believe the grape was known centuries before as Uva Grisa or Grisola and was the result of the domestication of local wild vines.

Wine writer Jancis Robinson in 2014 said, “The man who first put Barbera on a pedestal, or at least demonstrated that it was capable of making serious wine rather than local mouthwash, was the late Giacomo Bologna of the Braida estate whose Bricco dell’Uccellone was the first internationally marketed Barbera. The wine, which has since been followed by hundreds of increasingly expensive imitators, owed its distinction to two factors, much lower-than-usual yields and ageing in French oak barriques”.

A jaunt Down Under

It is believed by Australian growers of Barbera that the variety first landed on Australian shores in the 1950s and ‘60s.

Wine Australia’s 2019 varietal snapshot report accounted for roughly 110 hectares of land under vine to Barbera, based on 2015 figures.

Over 600 tonnes were crushed in 2019, 69 percent of which was crushed in the Riverina, 9% in the King Valley and 4% in McLaren Vale.

In the vineyard

Barbera is a vigorous variety and capable of producing high yield figures if not managed appropriately. Its excessive yields can weaken fruit quality and accent the variety’s natural acidity and sharp character profile.

The variety tends to ripen about two weeks ahead of another Italian wine staple, Nebbiolo, in Piedmont, and two weeks after Dolcetto – a rich, round yet soft fruit which crafts wines with distinct aromatics of blackberry and plum with a bitter almond after taste on the palate.

Barbera tends to be quite versatile in the soils it can grow well on, but will thrive most in less fertile calcareous soils and clay foam (Italian Wine Connection 2018).

The variety isn’t too widely planted in Australia, but those who grow the variety may have some viticultural challenges, according to one McLaren Vale winemaker.

Duncan Lloyd from Coriole Vineyards says the variety suits the Australian climate well, perhaps more than other Italian varieties.

According to Lloyd, The variety is quite fruit forward and juicy and has a herbal aspect to its character in some growing conditions. He says that in higher altitudes, he has noticed some more herbal qualities in Australian Barbera.

“It was in the late ‘90s when our Barbera was planted to trial,” Lloyd said, “It was planted around the same time as Nebbiolo, which turned out to not be as suitable to the region as Barbera”.

“It is susceptible to extreme heat, though, and some disease pressure, but it can be site specific.”

Hunter Valley producer Margan Wines was the first in the region to adopt the variety into its own vineyard in Broke Fordwich at its Ceres Hill property.

Margan Wines has just completed its 20th vintage with Barbera, having first planted the variety in 1998 using cuttings taken from the original Montrose Mudgee vineyard planted by Carlo Corino back in the 1950s.

Andrew Margan, owner and chief winemaker of Margan Wines in the Hunter, says the variety takes some time to acclimatise to Australian conditions, in his experience.

“As a young vine, it used to defoliate with extreme heat conditions,” he said, “However, as it has aged, it is now appearing to cope much better”.

He says Barbera is generally quite disease resistant and “our clone tends to distribute fruit so that bunches don’t sit one on top of the other, and the berries are quite loose”, making bunch rot rare.

“It doesn’t seem to mind wet weather and continues to ripen under waterlogged conditions.”

Margan has worked with Barbera across the Hunter Valley, Mudgee, Orange, the Barossa Valley and McLaren Vale. He says that, in Australia, the variety isn’t necessarily suited to one particular region over another, but that each region shows its character in the wines produced.

However, he says the characteristics the Hunter Valley brings out in the variety are quite unique.

“[There’s] no such thing as a ‘best’ region for me,” he said, “[Each region’s Barbera] is different and represents the individual regions’ particular growing characteristics. I have good and bad grapes from all the areas I worked with it.”

Margan says his Barbera block (planted in Broke Fordwich) is managed using VSP with permanent mid row sward and is managed using an undervine cultivation machine.

Margan spur prunes his Barbera to 16-20 buds per arm, however he is currently in the process of cutting the vines back to canes.

In the winery

Barbera is naturally acidic and high in tannin levels, but if managed correctly in the winery, can produce bright and fresh wine to pair with delectable Italian cuisine.

In the 1970s, a French oenologist – Emile Peynaud – recommended Barbera producers use small oak barrels for fermentation and maturation (Italian Wine Connection 2017).

This was suggested in order to add a subtle oaky characteristic to the wine, which allowed limited levels of oxygenation to occur through maturation, letting the single varietal wine soften that way. Peynaud discovered that the polysaccharides in the oak increased the variety’s richness.

Some winemakers will use Barbera as a blending variety with red grapes that may lack those acidic and tannin levels themselves, to make a softer, more rounded and potentially more balanced wine, but Margan says that it is a variety best crafted into a single varietal wine.

“Over the years we have looked at blending options but at the end of the day, because the wine is shaped around its acidity rather than its tannins, it really needs to be left alone and not blended,” he said.

“I ferment in closed stainless steel to two Baume and then press into stainless steel for malolactic (malo) fermentation.

“Post malo, the wine is run into one and two year old barriques for three months with some left in stainless. Given the low tannin content of the variety, the use of oak isn’t to soften the wine as such, so oak is not the answer for this variety.”

Margan says that there has been a couple of issues with Barbera in the winery, but there are ways to work around it.

“I have had Brettanomycese enter the winery twice from the vineyard and both times it was traced back to the Barbera,” he said.

“With that knowledge, we ensure we increase the use of SO₂ during the picking and crushing. Otherwise, as a low tannin and high acid variety, I look at acid levels for picking times as we would normally have colour and flavour ripeness present whilst having TA (tannin) levels above where we would pick.

If Barbera is presenting some issues in the winery, Margan’s ‘top tip’ is to “not pick it without getting your acid under 9 TA”.

Australian Barbera wines are often somewhat similar to those from Italy –

the similarities, of course, being the high acidity and savoury fruit flavour profile.

Margan’s Barbera is the best-selling red wine at his cellar door, which has given him confidence to plant an additional six acres of Barbera vines, bringing his block total to 18 acres.

“Barbera is a great variety for the Hunter,” he said, “It is not prone to disease and can ripen in wet years so, all in all, it works very well here”.

Market experience

Italian Barberas are imported frequently into Australia. One importer, who has been working with Italian varieties since the mid-1980s, and Barbera specifically since the mid-1990s, David Ridge, says the wines aren’t nearly popular enough here as they should be.

“While I couldn’t really say how much Barbera is sold in the Australian market definitively, it’s not enough!” he said.

“However, Barbera is growing in popularity and is inexorable.

“I honestly see it as one of the next big things – a serious niche – at least the size of something like Fiano, if not Sangiovese, in time.”

Ridge’s fondness of the variety, he says, is somewhat perplexed by the reality of its popularity here, with other Italian varieties performing better than Barbera, which he argues is a much better fit to Australian drinking habits.

“It could be lacking a bit in the personality department in truth – many of us thought the following behind Barolo/Nebbiolo/Piedomont wines, and the growth of that trend as a wine, food and tourism entity, should bring Barbera along for the ride,” he said.

“After all, it’s what they drink there in the restaurants and piazzas. Barbera’s following here has been harder to increase than I expected or hoped for, which is strange considering its simpler sibling Dolcetto seems to sell better

here overall.

Barbera is a variety so well-suited to Australian dining,” he continued, “It’s light and mid-weight, it’s fresh, fruity and zingy”.

Barbera has mostly been very accessible, easy to open and enjoy, and very, very adaptable with a wide range of foods – seriously weighty cuisines like Mediterranean, Malayasian or Morroccan.

“This may be where the confusion lies in Barbera’s variation. Barbera can also be a deadly serious wine. It can be complex, age-worthy and able to speak of its terroir.”

“Frankly, I get my Barbera fix (I use it more than once-weekly in my household) from Piemontese versions.

“But until recently, and while I still strongly believed in Barbera’s future here, I had stopped looking and subsequently had dismissed local Australian offerings as too much: whether it was to do with oak or uncontrolled ripeness; I thought they were without personalities, structure or enough of a savoury finish.

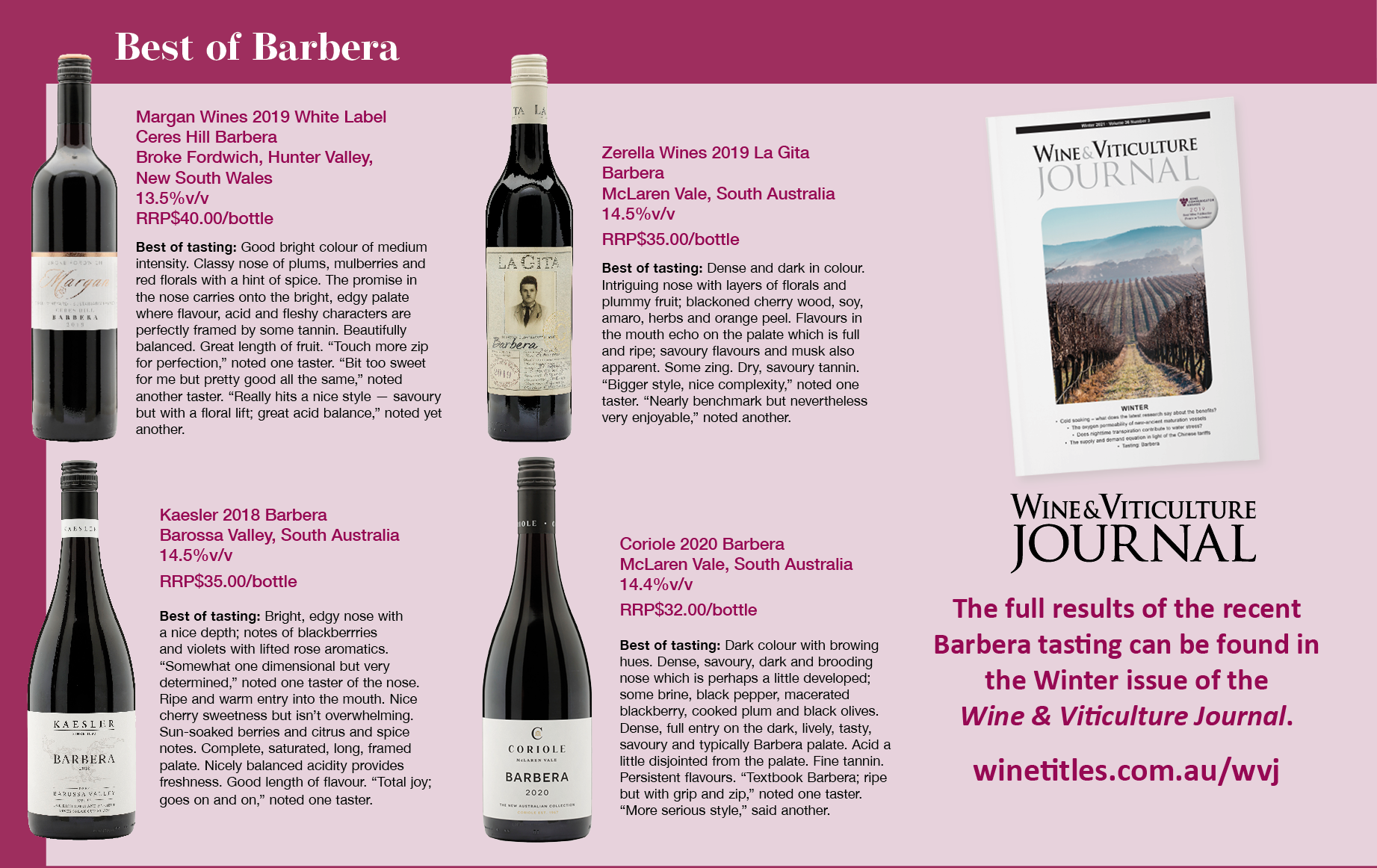

“But a recent Wine & Viticulture Journal tasting was a real eye-opener,” he continued.

“Nearly every one of the 20+ wines was drinkable or a lot better than that, were authentic (i.e., they were recognisable as the variety and were not that far behind the four Piedmont versions in the tasting as benchmarks).

“In fact, the tasters all agreed, it was one of the strongest style/varietal tastings ever experienced. Few other wine line-ups could have been so almost universally acceptable or better.

“The best versions moreover, while not being confused for Italians or quite as good as the best Italians, were super. We are underway with Barbera now, for sure!”

As of Wine Australia’s 2019 Variety Snapshot report, about 56,000 litres of Australian Barbera were exported, which sits lower than the figures for 2017-18. The UK sat as the top export destination for Australian Barbera and Barbera blend wines in 2019, taking 57% of Australia’s total Barbera export volume.

References

D’Agata, I. (2014). Native wine grapes of Italy (p.188). University of California Press. Accessed 31 May 2021, www.google.com.au/books/edition/Native_Wine_Grapes_of_Italy/y3_8AgAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Barbera. Italian Wine Connection (2018). Retrieved 31 May 2021, www.italianwineconnection.com.au/pages/barbera

L. Sweet, N. (2018). Barbera Finds a Second Home in California. Winegrapes of UC Davis. Retrieved 2 June 2021, www.fps.ucdavis.edu/grapebook/winebook.cfm?chap=Barbera

Robinson, J. (2014). Barbera. Jancisrobinson.com. Retrieved 31 May 2021, www.jancisrobinson.com/learn/grape-varieties/red/barbera

Wine Australia. (2019). Variety snapshot 2019 – Barbera. Wine Australia. Retrieved 31 May 2021, www.wineaustralia.com/getmedia/a73ff8df-0063-43c8-95d7-046892d6ff32/Barbera-snapshot-2018-19.pdf

Current Winejobs listings

New South Wales

Cake Wines

Cumulus Vineyards

David Hook Wines

Grove Estate Wines

Hart & Hunter

Lillypilly Estate Wines

Monument Vineyard

Mount Broke Wines

Piggs Peake Winery

Ravensworth

Saltire Estate

Skimstone Wines

Splitters Creek Vineyard

Topper’s Mountain Wines

Vico Wines

Zappa-Dumaresq Valley Vineyard

Berton Vineyard

Catherine Vale Wines

Centennial Vineyards

Cupitt Wines

Margan Winery &

Restaurant

The Little Wine Company

Vale Creek Wines

Pepper Tree Wines

South Australia

Architects of Wine

Bellwether

Belvidere Winery

Bremerton Wines

Chain of Ponds Wines

Chalk Hill Wines

DiFabio Estate Wines

G Patritti & Co.

Hastwell & Lightfoot

Henschke

Hollick Wines

Longview Vineyard

Mordrelle Wines

RedHeads Wine

Richard Hamilton Wines

Scarpantoni Estate Wines

Sevenhill Cellars

Unico Zelo

Vigna Bottin Wines

XO Wine Co

Adelina Wines

Alpha Box & Dice

Angas Vineyards

First Drop Wines

La Prova Wines

Landhaus Estate

Amadio Wines

Loom Wine

Victoria

Amulet Vineyard

Beechworth Wine Estates

Gapsted Wines

Glenwillow Wines

King River Estate

La Cantina King Valley

Merkel Wines

Michael Unwin Wines

Mount Langi Ghiran

Mount Towrong Vineyard

Pasut Family Wines

Serrat

Seville Hill

Tallis Wine

TarraWarra Estate

Yarra Vale

Chrismont

Dal Zotto Wines

King Valley Wines

Michelini Wines

Rob Dolan Wines

Sam Miranda Wines

Santolin Wines

Western Australia

Bella Ridge Estate

Bridgetown Winery

Moojelup Farm

Thomson Brook Wines

Vineyard 28

Queensland

Golden Grove Estate

Tasmania

Frogmore Creek Wines

Current Winejobs listings