Vintage 2021 – observations from the AWRI helpdesk

- Original article found in the Wine & Viticulture Spring 2021 issue

By Adrian Coulter, Ben Cordingley, Geoff Cowey, Robyn Dixon, Marcel Essling, Matt Holdstock, Mardi Longbottom, Liz Pitcher, Con Simos and Mark Krstic, The Australian Wine Research Institute, PO Box 197, Glen Osmond, South Australia 5064

The AWRI helpdesk responds to technical issues encountered by Australian grapegrowers and winemakers, identifies the root causes of problems and provides research-based, practical, up-to-date solutions. Monitoring the technical trends encountered across the nation’s wine regions over the growing season is a useful way to identify when information or assistance is required, at either a regional or national level. Support is then provided via eBulletins, the AWRI website, webinars or face-to-face extension events. This article examines some of the conditions experienced across the nation during vintage 2021 and the growing season leading up to it, and some of the technical challenges encountered.

Identifying key technical issues

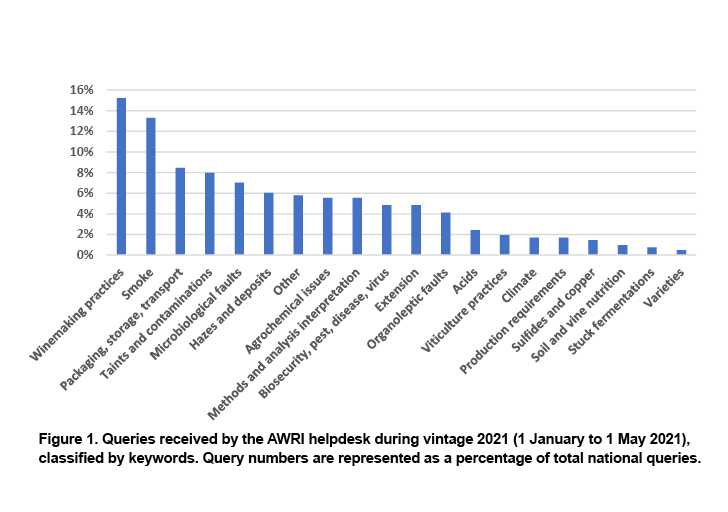

The AWRI helpdesk provides confidential advice and support to Australian grapegrowers and winemakers and is in a unique position to track the technical issues that emerge each vintage. During vintage 2021 (between 1 January and 1 May) the helpdesk received more than 400 enquiries (Figure 1) and conducted 37 small-scale investigations to identify the underlying cause of technical issues reported by winemakers and growers.

Pre-vintage

On 29 September 2020, The Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) declared that a La Niña event would occur during the 2020-21 growing season and bring with it wetter-than-average conditions. The La Niña peaked in late January 2021 and became inactive by March 2021. This weather event saw above-average rainfall throughout much of Victoria, the Hunter Valley, much of the west and south of New South Wales and southern South Australia, particularly from December 2020 to January 2021. The rains in many cases were timely and assisted with a slow and delayed ripening season. The wetter-than-normal season was also a relief in many cases, breaking the extended drought that had been experienced on the east coast for several years, replenishing vines, water storages and stream flows.

The AWRI held a webinar early in the season with Dr Paul Petrie from SARDI comparing the forecast La Niña event with previous events. There was concern that demand for fungicides registered for downy mildew would exceed supply and contingencies were prepared, but in the end these were not required. Botrytis outbreaks were reported across regions in Victoria and NSW and the AWRI later issued two eBulletins and held two further webinars on management of late-season botrytis in the vineyard and winery; however, the helpdesk did not observe an upswing in queries regarding increased disease pressure in vineyards or an increase in botrytis-affected wines.

Extreme multi-day rainfall events in late March affected many parts of eastern Australia and on the back of a La Niña event caused some flooding, but by this time the affected regions had mostly completed harvest. These rain events were the result of a different event, a blocking high pressure system in the Tasman Sea and a low-pressure system off north-west Australia feeding a large volume of moist tropical air into eastern Australia.

The La Niña event brought generally cooler growing conditions across south-eastern Australia. South Australia had its coolest summer in 19 years. Western Australia, after a dry winter in 2020, also reported a cool and wet spring followed by a mostly dry summer, but with some summer rain events causing humidity. The summer was the coolest summer in the last 15 years with harvest extending into April but completed before a cyclone event occurred mid-April.

Due to the generally cooler and longer ripening season, many producers experienced even ripening, with fruit flavour and tannin ripeness occurring before sugar ripeness. Fewer heatwaves and an extended growing season also saw fewer stuck fermentations and associated problems, possibly because producers had both time and tank capacity to manage ferments appropriately rather than being challenged by vintage compression. Higher acidity and, in many cases, double the typical concentrations of malic acid have been reported, resulting in high initial titratable acidities in must and subsequent larger-than-expected pH increases post-malolactic fermentation.

Based on the mild seasonal conditions across the country, good rainfall throughout the season and minimal seasonal challenges, producers have reported both exceptional fruit quality and high yields. Wine Australia’s national vintage survey has estimated an Australian winegrape crush of 2.03 million tonnes, the largest ever recorded, 17% above the 10-year average of 1.74 million tonnes (Wine Australia 2021; also see page 73 in this issue of the Wine & Viticulture Journal).

As for last vintage, the COVID-19 pandemic put pressures on labour availability, particularly for smaller growers and where hand picking was required, with fewer international seasonal workers available than usual and restrictions on travel across state borders. However, the cooler season and a drawn-out harvest did allow additional time for resource planning within regions.

Bushfires and planned burns

Thanks to the cooler season, there were fewer extreme temperature days and a generally lower risk of bushfires — a welcome relief after the 2020 season. Despite this, fires did occur in the Adelaide Hills (Cherry Gardens) and the Limestone Coast (Blackford), with smaller spot or grass fires in the Barossa Valley and McLaren Vale, South Australia, and Wooroloo in the Swan district of Western Australia. A forecast wetter 2021 winter after previous rain events raised the potential of a shorter window of opportunity to conduct planned burns to reduce bushfire risk. Several states therefore brought forward the start of their burns to early March, which caused concerns from neighbouring wine regions with fruit still on the vine. The AWRI worked with state and regional bodies to provide accurate information on controlled burns and their impact on viticulture to support communications with organisations conducting burns. A large number of queries on smoke taint answered by the helpdesk were also due to wineries processing 2020 wines and investigations of smoky sensory characters developing in wine with bottle ageing.

Other trends

An increase in helpdesk queries categorised under ‘winemaking practices’ related to wineries seeking information on practices including carbonic maceration, skin contact, water addition, fortification, sweetening, use of dried grapes in ferments, fining, aeration of red ferments and nutrient management and requirements of ferments. One-third of the ‘packaging, storage and transport’ queries related to the use of sulfur dioxide (SO2), with queries covering appropriate concentrations for microbiological control, particularly for Brettanomyces yeast, typical losses of SO2 over time during bottle maturation or wine ageing, SO2 removal due to over-additions during vintage and SO2 bleaching of young red wines.

‘Taints and contaminations’ queries included the common occurrences of brine leaks, hydraulic oil contaminations and burnt pump stators. Other contaminations were caused by the use of non-standard wine vessels or equipment, contaminations of winemaking materials and facilities during the mouse plague across New South Wales and Victoria, musty taints from the use of tainted dry ice, indole development in sparkling ferments and the potential for 2-isopropyl-3-methoxypyrazine (responsible for ‘herbaceous’ or ‘green’ flavours) being imparted into wine from ladybirds. Examination of microbiological queries indicated some wineries reported higher acetic acid production in some white ferments this vintage, possibly due to elevated loads of microorganisms or botrytis on fruit which were not obvious by visual assessment.

Biosecurity

The pest insect fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda, was first detected in northern Queensland in January 2020 and later in NSW in November 2020. This highly invasive pest has the potential to feed on grapevines but its behaviour is not well understood. Chemical controls were made available via Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority permits but were not required. A Queensland fruit fly (QFF) outbreak in the Riverland was declared in December 2020, affecting winegrape growers, wineries and those involved in the movement of winegrapes. In early 2021 outbreaks of Mediterranean fruit fly and QFF in metropolitan Adelaide also affected the movement of grapes between vineyards and wineries.

Looking towards vintage 2022

The El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) system is currently neutral. A negative Indian Ocean Dipole, however, has forecast warmer sea surface temperatures in the eastern Indian ocean and north of Australia which are likely to lead to wetter-than-average conditions this winter and into spring for south-eastern Australia, with more neutral conditions forecast for Western Australia (BOM Climate Outlook July-September 2021).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Australia’s grapegrowers and winemakers through their investment body, Wine Australia, with matching funds from the Australian Government. The AWRI is a member of the Wine Innovation Cluster in Adelaide, South Australia. The authors thank Ella Robinson for her editorial assistance.

References

Bureau of Meteorology website: www.bom.gov.au/climate/outlooks

Wine Australia 2021 Vintage Report. Available from: https://www.wineaustralia.com/market-insights/national-vintage-report

LeLacheur, P. (2021) Vintage Report Part 1: 2021 brings relief to Australian grape and wine producers Aust. N.Z. Grapegrower Winemaker 690:17-35.

Current Winejobs listings

.

This post was originally featured in the Spring 2021 issue of the Wine & Viticulture Journal.

To read more articles like this, subscribe online here.