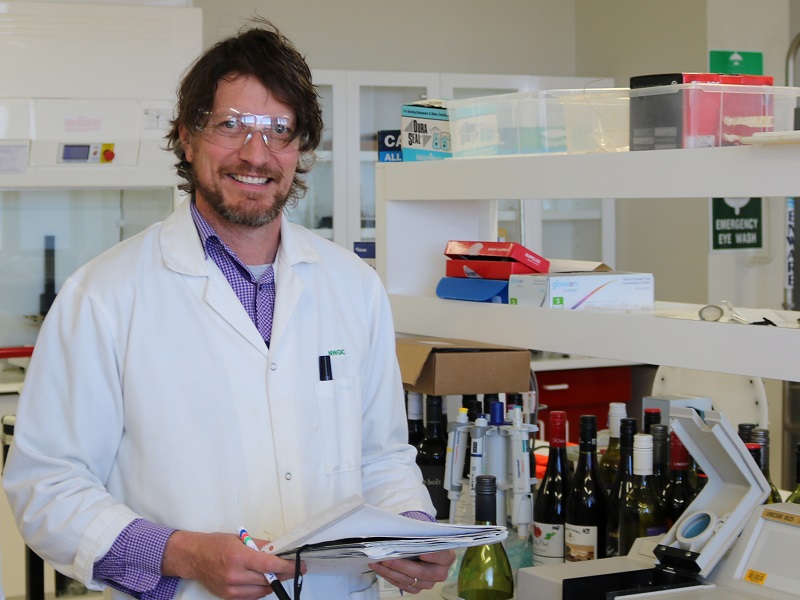

Journalist Eleanor Danenberg spoke to one of the Australian researchers behind a new method for assessing copper in white wine that can be carried out by wineries of any size use standard laboratory equipment.

A new methodology that makes it easier for wineries to assess copper (Cu) in white wine has been developed through a collaboration between the National Wine and Grape Industry Centre (NWGIC) and the Australian Wine Research institute (AWRI).

Revealed by Dr Andrew Clark, Charles Sturt University senior lecturer in wine chemistry, in the ‘Fresh Science’ session at the Australian Wine Industry Technical Conference in July, the method measures free, bound and total Cu concentrations using a spectrophotometer.

Previously, smaller wineries haven’t been able to readily measure total Cu concentrations without sending samples away for analysis.

“The method we’ve developed enables wineries to conduct routine quantification of total Cu in white wine using standard spectrophotometric equipment generally found in most wineries, and using the same equipment to assess the different forms of Cu in wine,” explained Clark, whose research team includes Nikolaos Kontoudakis, also from the NWGIC, and Mark Smith, Paul Smith and Eric Wilkes from the AWRI.

“The measurement of total Cu in wine can be of interest for a range of reasons for a winemaker. It can provide a better guide for winemakers if they are making additions of Cu to wine, and thereby may limit problems associated with high Cu concentrations and trade barriers. Cu is also active in accelerating the rate of oxygen consumption in a wine, leading to faster losses in sulfur dioxide and potential changes in wine colour for a given amount of oxygen ingress.”

The method involves the addition of a reagent (bicinchoninic acid/BCA) to white wine that binds Cu present in the wine to form a purple coloured complex. A spectrophotometer is used to objectively measure the extent of purple coloration formed in the wine. The more intense the purple colour after addition of the reagent, the more Cu in the white wine.

To determine the total amount of Cu in white wine, silver (Ag(I)) must also be added in order to enable the release of copper from other strong binders of Cu in white wine, and to enable efficient binding of Cu by BCA.

“We believe the Ag(I) is essentially swapping positions with Cu in sulfide complexes (i.e. 2Ag(I) + CuS becomes Cu(II) + Ag2S),” Clark says. “If Ag(I) is not added to white wine during the measurement then the Cu measured by the BCA reagent is predominantly Cu in the white wine that is not bound to sulfide (usually a minor fraction of Cu in white wine). We term this fraction of Cu the ‘free Cu’. The difference between the measures of total Cu and free Cu provides bound Cu, which is the Cu bound to sulfide.”

For red wine, it’s necessary to remove the colour of the wine prior to analysis, he explained. This is performed via digestion at 80oC with hydrogen peroxide and sodium hydroxide. Once performed, BCA is added to the digested red wine (now colourless or slightly yellow), and the total Cu concentration determined. He said Ag(I) addition is not required for Cu determination in red wine as the digestion removes the sulfide from binding to Cu.

Clark said the measurement of free Cu in red wine is trickier, “but we are currently finalising the methodology for the determination of free Cu in red wine with the BCA reagent”.

Until now, only larger wineries or research institutions with access to large infrastructure equipment, such as flame atomic absorption spectrophotometers (FAAS) or inductively coupled plasma techniques (ICP-OES [inductively coupled plasma with optical emission spectroscopy] or ICP-MS [ICP-mass spectroscopy]), have been able to routinely measure total Cu in wine, Clark said, and even then they cannot easily measure free Cu.

Clark said current methods to measure free Cu in wine are more research orientated and aren’t suited to wineries; they either require electrochemical equipment using a method that is labour intensive and prohibitively slow, or they require the same instrumentation as for total Cu (FAAS or ICPOES) in combination with labour intensive sample pre-treatment.

Better track copper in wine, minimise additions

Clark believes the BCA measurements of free and total Cu in wine will enable wineries to better track the amount of Cu in their wines, and to also perhaps minimise any additions made in the winery.

“The measurement of free Cu is a new concept for wine production and research has shown an inverse relationship with sulfidic-off aromas in wine. A survey of 50 wines showed that wines above 0.025mg/L free Cu had no free hydrogen sulfide (that not bound to metals) accumulate above the aroma threshold (above the level you can smell), while some wines below this level of free Cu had significant accumulation of hydrogen sulfide.”

He said the complication is that the free Cu present in the wine at bottling can decrease during the bottle ageing of wine in low oxygen conditions. Research is still being conducted to assess how quickly this occurs.

The decrease in free Cu in wine during bottle ageing is indicative of Cu sequestering sulfide from some precursor in the wine, Clark said. He advised wineries may find it useful to assess how quickly their wines bind to free Cu once bottled. Whether this may also provide targeted guidelines for free Cu levels in wines for subsequent vintages is the subject of future research.

Clark said the new method of measuring total and free Cu was an improvement on current measurement methods because it can be conducted in any winery with a spectrophotometer, a piece of equipment most wineries already have for measurements of wine colour and for enzymatic kit analysis, such as for determining the malic acid, glucose, or fructose content in wine.

Currently there are no methods for the measurement of free Cu in wine that can be performed by any winery (regardless of access to FAAS and ICPOES), said Clark.

“This would be the only practical method for the measurement of free Cu in wine and it can measure total Cu as well,” Clark said.

He said most of the equipment and reagents required for the method would already be in a winery. The exception would be silver nitrate and the BCA reagent. However, Clark noted these are relatively cheap and for a total cost of around $200-300 (for BCA and silver nitrate) would enable several thousands of total and free Cu determinations. He added that ideally a glass cuvette (40mm) would also need to be purchased for use in the spectrophotometer.

When comparing this cost with other methods, Clark estimates the instrumentation for FAAS analysis would cost in the order of $20,000- $40,000, and would also require lamps, gases (air, acetylene) and maintenance. He estimates the alternative of ICPOES analysis would cost around $80,000- $120,000, and require argon for operation, and frequent maintenance.

Clark said the new method would suit wineries of any size, adding “for total Cu determination, if we have only a few wines to analyse, we find it even quicker and more preferable than using ICPOES or FAAS”.

Another benefit of this method is that very little specialist equipment is required, he said; only a spectrophotometer and micropipettes (to deliver volumes ranging from 0.05-0.5mL). Clark added the only ‘catch’ is the cuvette.

“To achieve the measurement of particularly low concentrations of Cu (0.02mg/L) a glass cuvette of 40mm is best used. Although these are not so expensive, some spectrophotometers do not fit them [the typical cuvette used in a spectrophotometer is only 10mm]. Often older spectrophotometers have greater flexibility in the cuvettes they can fit.”

“If a standard 10 mm cuvette is used then total Cu concentrations down to around 0.08-0.10mg/L can be measured, while if a 40mm cuvette is used then concentrations down to 0.02mg/L can be measured. Given many commercial wines have more than 0.1mg/L Cu, using a 10mm cuvette would still be okay in many cases.”

Clark said free Cu was usually much lower than total Cu in which case a 40mm cuvette would definitely be necessary to measure the concentrations around 0.025mg/L.

The method for total Cu determination in white wine can be found online here.

This article was first published in the November 2019 issue of the Australian & New Zealand Grapegrower & Winemaker. To subscribe from as little AUD$55 a year for 12 issues click here