Laying the groundwork for a subsequent article in the Winter issue of the Wine & Viticulture Journal, which will canvass what can be done in the vineyard to limit carbon emissions, Tony Hoare outlines what we currently know about the wine industry’s carbon footprint.

The carbon economy is making headlines at the moment as many developed countries contemplate carbon emissions reduction targets and timeframes. In September 2022, the Australian Government passed legislation to set an emissions reduction target of 43% and net zero emissions by 2050.

Many industries realise the inevitability of a fast-approaching carbon economy with many already examining technology and practices as they prepare to decarbonise production to meet future targets of reduced and zero carbon emissions.

Unfortunately, in the meantime, consumers bear the financial pain as sectors transition from cheap fossil fuels to renewable energy resources, passing on increased cost of goods, food, fuel and energy.

Grapegrowers are not immune from the effects of this developing carbon economy and are currently experiencing record high electricity, fuel and fertiliser prices that are increasing the costs of production at a time when the market for winegrapes is difficult and unpredictable.

To make matters worse, they are also having to contend with the difficult growing conditions associated with increased levels of atmospheric carbon and other greenhouse gases which are contributing to a warmer planet, resulting in less predictable climate patterns and an increasing occurrence and intensity of extreme weather events.

For grapegrowers, it seems there is no escaping the carbon emissions issue as social, regulatory and market pressures grow. Scientists and politicians now agree that reducing greenhouse gas emissions is the best (and only) way to hopefully address the problems associated with a warming planet Earth.

The challenge of achieving this has fallen to our generation to take action and begin to elicit change. The economic cost of change will be relatively high and the benefits may not materialise for 30 or 40 years (Garnaut review 2011).

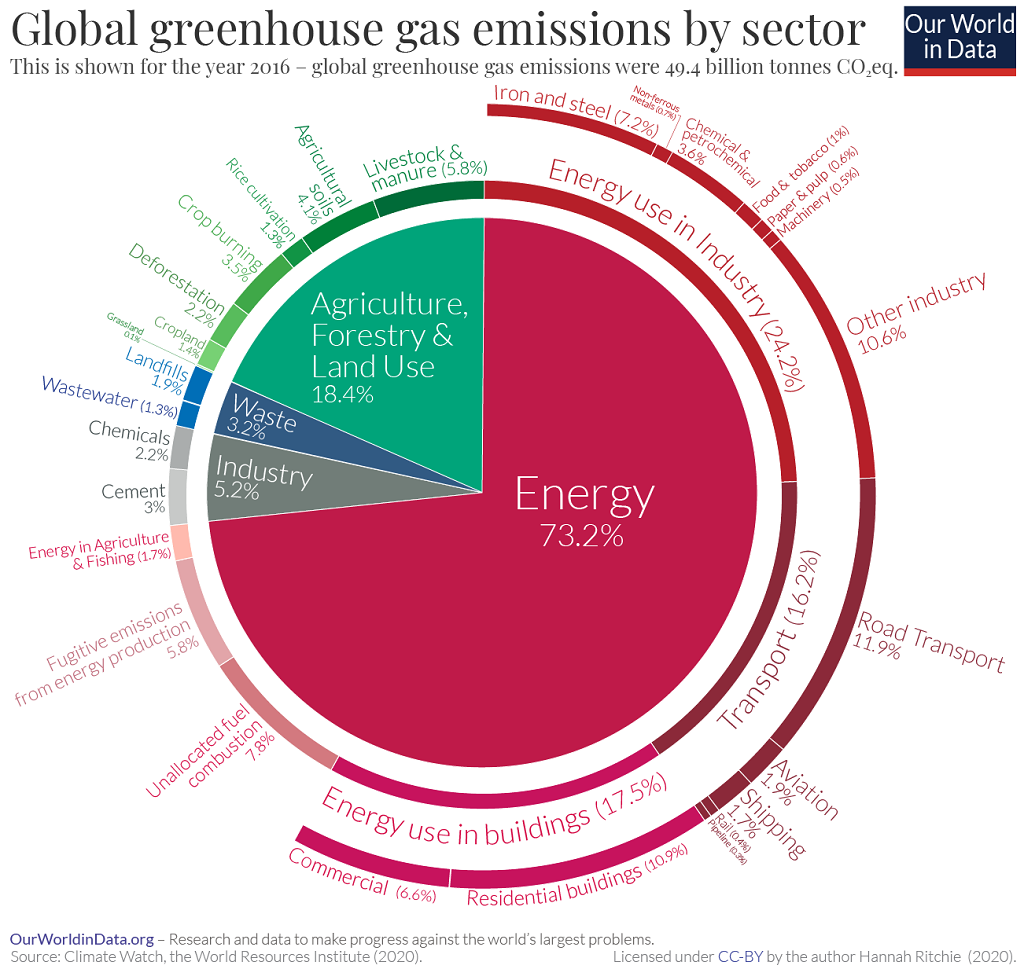

On a positive note, when compared with other sectors, the wine sector is not really a significant contributor to CO2 emissions. Electricity and heat are by far the largest contributors to global emissions (73.2%) (Climate Watch, the World Resources Institute 2020).

To “assess the overall environmental footprint of vitivinicultural production in order to develop appropriate action plans”, the International Organisation of Vine and Wine (OIV) in 2020 formulated the principles for a life cycle assessment (LCA).

The purpose of the LCA approach was to allow the identification of lifecycle stages or individual processes that are an environmental burden and can possibly be reduced or avoided (OIV website, 2022).

As this issue of the Wine & Viticulture Journal reveals (see page 34), the AWRI has recently updated its calculation of the LCA of Australian wine production with the carbon footprint breakdown of a bottle of wine (1.05kg CO2e/L).

The calculation shows transport and glass packaging make up approximately 74% of the total life cycle (a contribution increase of 6% compared to 2016) with grapegrowing and winemaking each contributing 13% (Hirlam et al. 2023). It is clear that the biggest issue facing the wine sector and its ambitions for carbon reduction is the use of glass bottles.

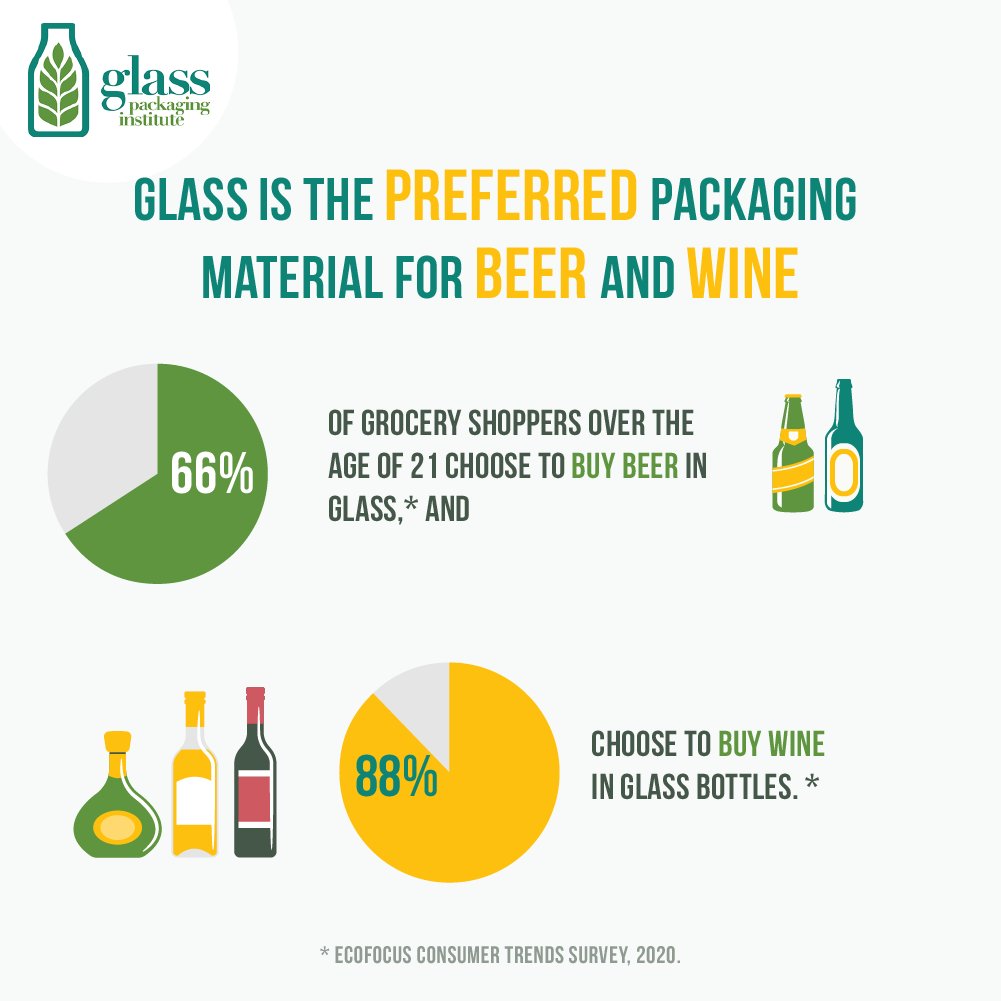

Glass is overwhelmingly the preferred packaging for wine by both producers and consumers worldwide. A recent survey conducted by Winetitles (2021) found only 19% of Australian and New Zealand wine producers are currently packaging their wines in glass alternatives.

Whilst 44% of wine producers considered packaging their wines in alternatives to glass for sustainability and improved ‘green’ marketing credentials, they chose glass instead due to concerns with ageing of wine longer than one year in bottle, production not being large enough to diversify, potential negative impact on wine quality, potential negative consumer perception to brand and a perceived lack of demand for alternative packaging to glass (Logan 2021).

Wine bottles are currently not included in container deposit schemes (CDS) operating in Australia. It is thought that inclusion would increase the recycling potential of glass wine bottles which currently have a high percentage ending up in landfill.

This is mainly due to issues associated with kerbside recycling where mixing bottles with other recyclables causes a situation where they cannot then be separated for recycling and end up in landfill.

If glass is collected through a deposit scheme, 98% of glass is suitable for recycling into new containers compared with 40% with single stream recycling where the glass is mixed with other recyclables (Glass Packaging Institute 2022). On the positive side, glass is infinitely recyclable and is made from natural ingredients.

However, on the negative side, it requires high energy inputs for production and its heavy weight compared with alternative packaging increases its carbon footprint when transported. It is thought that recycled glass can reduce the production costs of manufacturing wine bottles through a reduced energy requirement in manufacturing however this could not be verified.

The NSW Government is currently considering including wine bottles in its current container deposit scheme (CDS) which would see a $30 million tax placed on Australian wine producers in the state and around $100 million nationally with almost no environmental benefit, according to Australian Grape and Wine (agw.org.au).

The inclusion of wine bottles in a CDS would likely see more recycling of wine bottles and less landfill, however, the cost to industry must be weighed up so that any model adopted doesn’t become a financial burden to wineries.

Submissions to the proposal to include wine bottles in NSW’s CDS closed in December 2022 which should allow the wine sector time to respond and hopefully reach a compromise. ‘

Towards Australian grape and wine neutrality….the possible dream’ (Smart et al. 2020) was published with the aim of encouraging the Australian grape and wine sector to engage in a strategy of climate change mitigation. Two years down the track, Wine Australia has recently initiated a roadmap to zero emissions for the Australian wine sector with the aim of achieving net zero carbon emissions before 2050 (Wine Australia 2022).

The important first step of stakeholder engagement began in July 2022 with the appointment of Edge Environment. In the search for an emissions baseline, the AWRI estimated CO2 emissions for the Australian wine sector in 2017 to be 1.6 million tonnes (since updated to 1.38 million tonnes in the latest AWRI analysis, pers. comm. – Ed) which seems insignificant compared to domestic and international aviation which produced 22 million tonnes.

It is not clear if this figure included the offsets of vineyards and their ability to sequester CO2.

Vineyards sequester carbon from the atmosphere in vegetative components of the vine (fruit, leaves, shoots and permanent woody structures of the trunk and cordons) for a combined total of up to 0.8-0.9 tonnes of carbon per hectare.

Soil management in midrows and surrounding headlands, which contribute up to 80% of the vineyard surface, is also an atmospheric carbon sink. Although it is not mandatory for wine sector businesses to be carbon neutral at present, regulatory bodies’ new rhetoric with setting target outcomes and timeframes as well as the social licence/consciousness for manufacturers, especially in agriculture, have motivated some to take the early lead to enhance their green credentials.

USA-based wine company Jackson Family Wines, which owns wine businesses and vineyards in Australia, has created a roadmap to 2030 called ‘Rooted for good’ with one of the many objectives to achieve a 50% reduction in carbon emissions by 2030 and then become ‘climate positive’ by 2050. The pathway to becoming a net zero or carbon neutral business begins with a greenhouse gas emissions audit.

The Australian wine sector created a self-assessment calculator back in 2008 which is still relevant today (https://www.awri.com.au/ industry_support/sustainable-winegrowing-australia/carbon-calculator/).

Once a carbon footprint has been established then carbon neutrality can be achieved in two ways. The first is by decarbonising to reduce CO2 and other greenhouse emissions, which is mainly done by adopting new technology such as renewable energy or purchasing green power from a third party.

The second way is to offset greenhouse gas emissions though a carbon emissions trading abatement scheme. This is where things gets interesting and a ‘buyer beware’ advice is needed to avoid being accused of ‘greenwashing’.

As stated in the research report ‘Climate of the Nation 2022: Tracking Australia’s attitudes towards climate change and energy’, published by The Australia Institute: “At present, Australia does not have a comprehensive disclosure framework to verify progress towards net zero targets or the carbon neutral claims of companies.” (Quicke and Venketasubramanian 2022).

So, there is not the regulatory framework in government to support a legitimate carbon trading scheme using credits mainly from stored soil carbon, also known as an ACCU (Australian carbon credit unit).

In theory, farmers under the emissions reduction fund could trade ACCU credits to assist high greenhouse gas polluters reduce their greenhouse gas emissions footprint. In practice, the carbon farming initiative trial looking at the generation of ACCUs was only able to substantiate one soil carbon project generating ACCUs since the trial inception in 2014 (White 2022).

There are many issues around the practical implementation of such a scheme including attractiveness to farmers, financial incentives, regulatory framework, transparency and legitimacy of the scheme as well as the cost of measuring soil carbon and the possible disincentive for large greenhouse producers to decarbonise their own businesses.

The die is now cast and we are all going to be affected in one way or another by a new carbon economy over the next 20 to 30 years.

How that economy unfolds is still unknown, however early planning and careful implementation of change by the wine sector will undoubtedly lessen the impact severity and help the planet in the process.

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

Abbott, T.; Longbottom, M. and Wilkes , E. (2016) Carbon footprint of Australian wine. Poster, Australian Wine Industry Technical Conference 2016, https:// awitc.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/141_ Abbott.pdf

Climate Change Authority (2022) Coverage, additionality and baselines — lessons from the Carbon Farming Initiative and other schemes https:// www.climatechangeauthority.gov.au/publications/ coverage-additionality-and-baselines-lessons-carbon[1]farming-initiative-and-other-schemes

AWRI Carbon calculator https://www.awri.com.au/ industry_support/sustainable-winegrowing-australia/ carbon-calculator/

Government of South Australia (2022) Carbon Farming Roadmap for South Australia. https://pir. sa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/428893/carbon[1]farming-roadmap.pdf

Hemming, P (2022) The Australian Institutes Climate of the Nation Survey. The Australia Institute.

Hirlam, K.; Abbott, T. and Wilkes, E. (2019) Fermentation’s clean little secret. Poster, 17th Australian Wine Industry Technical Conference. https://awitc.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/60_ Hirlam_Fermentations-Clean-Little-Secret.pdf

Hirlam, K.; Longbottom, M.; Wilkes, E. and Krstic, M. (2023) Understanding the greenhouse gas emissions of Australian wine production. Wine & Viticulture Journal 38(2):36-38.

Logan, S. (2021) Wine industry voices taste for alternatives to glass bottles. Aus. NZ Grapegrower Winemaker 688:38-41.

Quicke, A. and Venketasubramanian, S. (2022) Climate of the Nation 2022: Tracking Australia’s attitudes towards climate change and energy. The Australia Institute. p46.0

Reux, J. (2022) When wine goes carbon free. La Revue du vin de France. https://www. larvf.com/quand-le-vin-passe-au-regime-sans[1]carbone,4804605.asp

Smart, R. (2019) Carbon footprints, wine and the consumer. JancisRobinson.com. https://www. jancisrobinson.com/articles/carbon-footprints-wine[1]and-consumer

Smart, R.; Bruer, D.; Collins, C.; Corsi, A.; Jeffery, I.; Karatonis, L.; Muhlack, R.; Oemcke, D.; Pike, B. and Wilkes, E. (2020) Towards Australian grape and wine industry carbon neutrality….the possible dream. Winetitles, September 14, 2020. https://winetitles.com. au/199176-2/

Wine Australia (2021) Carbon Neutral Claims – fact sheet. www.wineaustralia.com

White, R.W. (2022) The role of soil carbon sequestration as a climate change mitigation strategy: an Australian case study. Soil Systems 6(2):46 https:// doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems6020046

Tony is a viticulturist based in McLaren Vale, South Australia. He has a broad range of interest and experience in all aspects of viticulture and enjoys discovering new ways to improve the value and profitability of vineyards.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2023 issue of Wine & Viticulture Journal. To find out more, or to subscribe, click here!

Are you a Daily Wine News subscriber? If not, click here to join our mailing list. It’s free!